Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, whether through the mighty communal monuments of the Neolithic period such as Stonehenge, in the rich grave goods found in individual burials from the early Bronze Age onwards, or by the massive hillforts (like Maiden Castle) that typify the Iron Age.

SYMBOLS OF AUTHORITY

We cannot know what kind of people exercised power among the nomads who roamed Palaeolithic Britain (about 900,000–9500 BC).

They may have been the strongest hunters, or the wisest older men and women, or people with perceived spiritual gifts. Reindeer-antler ‘batons’ like those found at Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, Somerset, have been interpreted as their symbols of authority.

ORGANISATIONAL POWER

The settled farmers of the early Neolithic period (4000–3000 BC) left far more obvious symbols of power - or at least of considerable organisational ability. The construction of great communal tombs like the long barrows at West Kennet and Belas Knap needed thousands of hours’ work by many people. It has been estimated that the outer ring ditches of the roughly contemporary Windmill Hill, Wiltshire, required 48,000 person-hours to dig.

Such targeted effort needed management, and we do not know whether it was forced labour under hereditary rulers, or a genuinely communal enterprise. Nor do we yet understand the connection between the endeavour and the comparatively small number of men, women and children who were buried within the tombs (36 at West Kennet, perhaps only 15 at Wayland's Smithy in Oxfordshire). Were these the families and descendants of the organisers, or were they honoured for some other reason?

NEW POWER SYMBOLS

The construction of Silbury Hill and later stone phases of Stonehenge (about 2500–2000 BC) were infinitely more formidable feats of logistics. The transport of bluestones from south-west Wales and of the much heavier sarsens from the Marlborough Downs implies influence extending far beyond Salisbury Plain. So do the nearby burials of people from distant parts of Britain and, in the case of the Amesbury Archer (buried about 2400 BC), from the Continent.

The completion of great monuments such as Stonehenge must have conferred tremendous prestige on their patrons.

From the early Bronze Age, however, individual power and prestige were expressed in a new way: through the furnishing of burials in round barrows with magnificent grave goods. Few were more impressive than those at Bush Barrow near Stonehenge (1900–1700 BC), which included a lozenge-shaped gold breastplate, a huge bronze dagger with a handle inlaid with tiny gold pins, and a ‘sceptre’ with a fossil-stone head.

IRON AGE HILLFORTS

Whatever their defensive function, the hillforts that typify the Iron Age (800 BC–AD 50) were more straightforwardly visible symbols of power, whether of whole tribes or (more probably) of individual chieftains or dynasties.

Another means of expressing prestige was, seemingly, the public sacrifice of valuables like bronze shields by throwing them into rivers and bogs. Conversely, rich Iron Age burials are rare, a notable exception being Lexden Tumulus near Colchester. It was decked with prestigious goods revealing links with Rome, and datable to about 10 BC. Its occupant was probably Addedomarus, king of the local Trinovantes tribe, otherwise known only from his coinage – another new symbol of power.

IRON AGE HILLFORTS

Roman sources henceforth allow us to put names to rulers: Cassivellaunus, Caesar’s opponent in 54 BC; Cunobelin (Shakespeare’s Cymbeline); and his son Caratacus, who led the resistance to Roman invasion in AD 43.

They also describe rivalries between tribes, and even within dynasties.

The pro-Roman Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes, who divorced and deposed her anti-Roman husband, Venutius, and of course Boudicca of the Iceni, serve as reminders that power in late prehistoric Britain was not exclusively exercised by men.

More about Prehistoric England

-

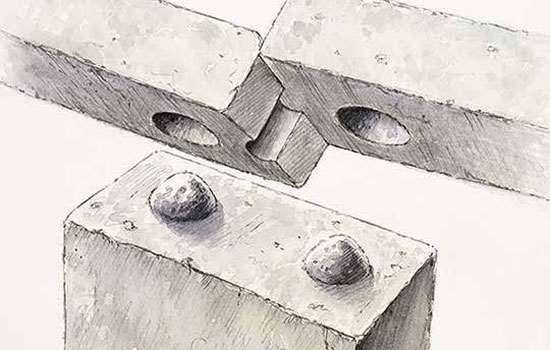

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Roman Invasion at Maiden Castle

Britain’s largest Iron Age hillfort was once regarded as a monument to the brutality of Roman invasion, but its story may be rather more complicated.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.