Romans: Networks

The Roman road network was vital for transport and trade, and was one of the Romans’ most enduring legacies: it would remain the skeleton of communications in Britain until the 18th century.

ROADS

Following the conquest, the Romans connected their cities and military bases with a network of engineered roads that stretched across Britain. These roads, with their well-known post-Roman names – such as Fosse Way and Ermine Street – are often still in use as highways. The word ‘street’ (from strata, meaning road) is one of the few Latin words to have remained in continuous use since the Roman period.

The linear monument on Wheeldale Moor, North Yorkshire, may be the only extensive stretch of original Roman road construction still visible – although its Roman date is now disputed.

THE CURSUS PUBLICUS

The roads were used by civilian traffic alongside the military: most villas and small towns developed in places well served by the road network.

The cities were responsible for the upkeep of the roads and the maintenance of the cursus publicus, the imperial communication service. This was a system of inns, stables and posting houses, together with horses, mules and wagons, all maintained at public expense for the use of imperial officials, so that they could travel as speedily and efficiently as possible across the empire. The courtyard building at Wall, Staffordshire, at the junction of Ryknild Street and Watling Street (which stretched from Verulamium – modern St Albans – to Wroxeter in Shropshire), is a surviving example of an official inn or mansio.

Despite its name, the cursus publicus was not for general use: private individuals could use it only by special permit.

WATER TRANSPORT

River transport, faster and cheaper than the roads, was used for the movement of goods – but leaves little archaeological trace. Traffic also ran along the coasts: seaborne traders carrying goods from all over the Roman world converged on London, and there was a vigorous movement of pottery, grain and other supplies from the south-east of England to Hadrian’s Wall, via London and then up the east coast.

Transport by sea was also the most rapid way for soldiers and imperial officials to travel between the capital and the Wall – they arrived at the port of South Shields. It was also, of course, the only means of getting from the Continent to Britain – hence the presence of a mansio at Richborough, Kent, one of the main ports of entry to Britain.

COMMUNICATIONS

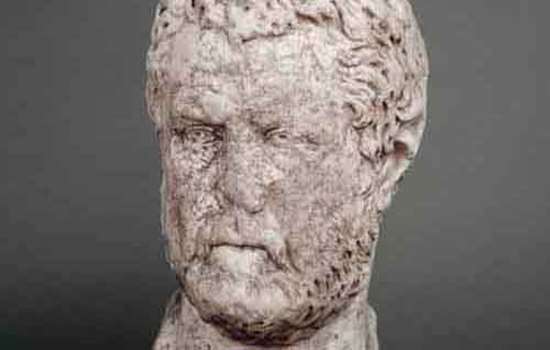

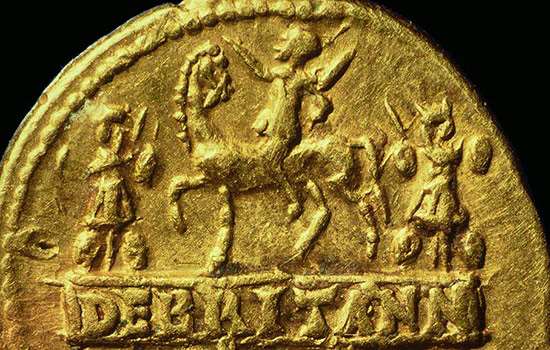

The information networks of the Roman Empire were of a sophistication that would not be matched until quite recent times. Most people in Roman Britain would have known what their ruler looked like, for example, because they would have seen accurate portrait busts on coins and on statues in cities and towns, which were based on official prototypes and erected by the civic authorities.

Official and civilian travellers could carry letters and other documents, either inked or inscribed into wax on small wooden tablets. Both coins and publicly visible stone inscriptions proclaimed the emperor’s titles and commemorated his achievements in written form.

LITERACY

Literacy was probably at its highest in urban and military circles. To what extent people in the small towns and countryside participated in the information network is uncertain.

The writing tablets from Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall, though, and the curse tablets – metal plaques on which individuals wrote messages to the gods to intercede on their behalf – so common at shrines in southern Britain, suggest that literacy in Latin, the common language of the western Empire, extended far down the social scale both in military circles and in the civilian south, except perhaps in the remotest countryside.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.

Roman Stories

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.