Religion in Roman Britain

Although they famously suppressed the Druids during their invasion of Britain, the Romans were largely tolerant of other religions, provided that the conquered populace incorporated the Imperial Cult into their worship. The Romans sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population. People worshipped these hybrid gods, together with ancient local deities and exotic new cults.

Roman Gods

The classical gods of the Graeco-Roman world, such as Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, and even the divine majesty of the emperor, were honoured and worshipped at temples in the cities of Britain, and at the forts of the army stationed in the province.

Adherence to this ‘official’ religion demonstrated loyalty to the emperor, and was a prerequisite for social advance. But almost everybody had a private religious life. Belief in local Celtic gods persisted, and mystery cults originating in distant corners of the empire gained followers too.

Local Gods

Both the Romans and most people in pre-Roman Iron Age Britain believed that as well as supreme or general gods, there were also local gods or spirits (genii) in every person and place. It made sense to honour and placate them.

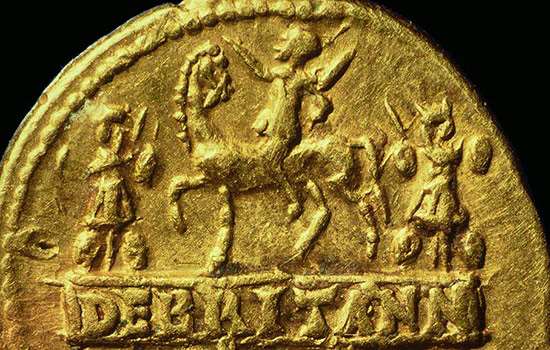

This meant that when the Romans came to Britain, there was no clash of belief systems. Instead, local gods were merged with the incoming Roman ones – a process known as syncretism. At Bath, the goddess Minerva was identified with the local god Sul, and similarly the Roman god Mars was identified with local war gods. In the Hadrian's Wall area he is found as Mars Cocidius and Mars Belatucadrus.

It is often impossible to be sure which of these Celtic deities existed in pre-Roman Britain and which were imports – via the Roman army – from other Celtic societies in north-west Europe, such as the goddess Coventina at Carrawburgh.

Old and New Beliefs

The persistence of pre-Roman Iron Age beliefs is seen in the significance afforded to horned gods, wet places, heads, and ritual wells and shafts. It is also evident in the occurrence of gods in groups of three, like the matres (mothers), and the three hooded deities (the genii cucullati) carved in stone at Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall.

Alongside their own gods, the Romans introduced a range of others from outside the classical pantheon. These included Mithras, an eastern god of light and rebirth, favoured by soldiers and some urban communities. His temples have been found at forts on Hadrian’s Wall, including Carrawburgh and Housesteads.

Another religion imported from a far corner of the empire would change the face of England forever.

Christianity

It is not certain when Christianity was introduced to Britain, but it became increasingly popular among the elite in the 4th century after the conversion of the emperor Constantine in AD 312. Villas were decorated with Christian iconography, like the mosaic found at Hinton St Mary. At Lullingstone Roman Villa in Kent a house-church was decorated with Christian wall-paintings.

Pagan traditions remained strong, though. There is evidence that pagan rituals continued in Lullingstone’s church building, and pagan shrines, often of pre-Roman origin, were built and embellished in large numbers across southern Britain (for example at Jordan Hill and Maiden Castle, both in Dorset).

These temples were focal points for the hopes and fears of rich and poor alike, and were dedicated to both Roman and native deities. Even quite humble people were literate enough to be able to write on lead ‘curse tablets’, which they nailed to the walls of shrines, inciting the gods to destroy those who had wronged or stolen from them.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.

Roman Stories

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

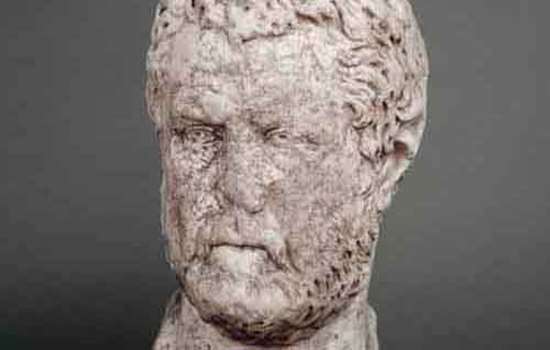

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.