MILBURGA’S FAMILY

Milburga’s father was Merewalh (d. c.685), king of the Magonsaete. His domain, a sub-kingdom of Mercia – the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that covered much of the midlands – encompassed the modern counties of Herefordshire and Shropshire. Merewalh converted to Christianity in 660, marrying Domne Eafe (d. c.700), a Kentish princess. Her lineage included King Ethelbert (or Æthelberht; d.616), who had welcomed St Augustine on his mission from Rome to convert the English in 597.

Milburga’s family was distinguished by its piety and sanctity. Her mother, and sisters Mildred (or Mildrith; d. c.700) and Mildgyth, all became abbesses and were destined to be venerated as saints, while Ethelred and Ethelbricht (d. c.670), her maternal uncles, were regarded as martyrs. Her father was a founder of monasteries, including Wenlock, Shropshire, in about 670–80.

A Double Monastery

Wenlock, then known as Wimnicas, was a so-called ‘dual house’, with a community that included both monks and nuns and had an abbess at its head. Monasteries of this type originated in the Frankish kingdom of what is now northern France: they were not uncommon between the 7th and 9th centuries. The most famous was at Chelles, where Mildred, Milburga’s sister, spent time as a nun. As at other dual houses, such as St Hild’s monastery at Whitby, the monks and nuns at Wenlock would have worshipped in their own churches. They would also have had separate dormitories and refectories.

Wenlock was initially subject to the monastery at Iken (Suffolk), which had been founded by St Botwulf (d.680), who was trained at Chelles. Wenlock’s first abbess was called Liobsind, a name that suggests Frankish origins.

Read more about early medieval religionMilburga’s Renown

Milburga succeeded Liobsind as abbess of Wenlock, and the abbey thrived under her leadership. The so-called Testament of St Milburga, which she composed towards the end of her life, details how she expanded Wenlock’s estates. This was thanks to gifts by princes, nobles and her own judicious purchase of lands. Milburga was acquainted with leading figures in the Anglo-Saxon Church, including St Theodore (d.690), Archbishop of Canterbury.

A letter written by St Boniface (d.754), an Anglo-Saxon monk and missionary to Frisia (Germany), shows the contemporary religious fame of Milburga and her monastery. Boniface describes a vision of the afterlife experienced by a monk at Milburga’s monastery, who while his brother monks were singing prayers over his corpse, ‘returned to [his] body at first light having left it at first cockcrow’. News of this miraculous event had spread widely: Boniface had learnt of it from Abbess Hildelith of Barking, while his letter recounting the events was addressed to Eadburg, a nun at Wimborne in Dorset.

Sainthood

Milburga died in or after 716 and was buried in the nuns’ church at Wenlock. She was soon venerated as a saint. The monastery at Wenlock was dedicated to her and several Anglo-Saxon abbeys kept a feast day in her honour on 23 February, probably the anniversary of her death. An early 11th-century list of the ‘resting places’ of saints says that her relics were still preserved at Wenlock.

By this time, however, nuns had long since ceased to be part of the community at Wenlock, which became a minster, with priests in charge.

The refoundation of Wenlock

Religious life at Wenlock was revived in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest thanks to Roger of Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, a leading Norman aristocrat. Between 1080 and 1082 Roger refounded the monastery as a priory for Cluniac monks. By this time the former nuns’ church at Wenlock was in ruins, the location of St Milburga’s grave and relics forgotten.

Despite their French origin (the monks came from the priory at La Charité-sur-Loire in Burgundy), the monks soon took an interest in St Milburga and her relics. Relics – the physical remains of saints, their clothing, possessions, or sometimes even simply objects which had come into contact with these – had a very important place in medieval Christian belief. Tangible evidence of a saint’s life on Earth, many were believed to have miraculous powers, especially the ability to cure illness.

Medieval cathedrals and monasteries often had large collections of relics. They kept the most important relics in specially built shrines or reliquaries – special containers often made of precious metal.

Milburga’s relics

Milburga’s relics were rediscovered in the summer of 1101. The events are described in a contemporaneous account purportedly written by Odo, the Cardinal Bishop of Ostia in Italy, who visited Wenlock to verify the discovery. Odo relates how the monks were disappointed to discover that a silver casket they hoped might contain St Milburga’s relics in fact held nothing more than ashes and old rags. This led them to wonder where her remains might be.

Around the same time one Raymond, a lay brother of the monastery, was helping to restore the ruinous church of the Holy Trinity, which had probably been that of the nuns. During his work, he discovered an old box containing a document written in English. This said that St Milburga’s grave was in this church, close to an altar now destroyed. After obtaining permission from the Archbishop of Canterbury, the monks set about excavating to find the relics.

But in the event, the grave was discovered by accident. On the night of 23 June, two boys playing among the church ruins fell into a pit. The next morning, the monks dug there, and found the bones of St Milburga exactly where the document said she was buried, close to an old altar. They washed the bones and placed them in a new shrine, or casket.

Miraculous cures

Pilgrims now flocked to Wenlock, and when several miracles occurred they were taken as confirmation that the relics were indeed those of St Milburga. Two people were cured of blindness, and two others of leprosy. Another person suffering from a wasting disease vomited a hideous worm after drinking water that had been used to wash the relics.

At about this time a Life of St Milburga was written, probably by Goscelin of Saint-Bertin, a monk renowned for his hagiographies (idealised saints’ lives). This recounts how Christ, working through the saint, restored a dead man to life; and how thanks to Milburga’s prayers, geese which were eating the abbey’s corn were banished, never to return – a miracle also attributed to other female saints of the Anglo-Saxon era, including St Hild of Whitby. The Life is also the source for the Testament of St Milburga.

Milburga revered

The monks’ church was dedicated to St Milburga and St Michael, whose images ornamented the priory’s seal. St Milburga’s relics were ‘translated’ or moved to a specially built shrine in the priory’s church, probably behind the high altar. A 13th-century source describes how these relics were carried in procession outside the monastery at Whitsuntide (the seventh week after Easter).

The monks clearly held St Milburga in great reverence. A 13th-century manuscript from the priory’s library (now at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge) contains a Life of St Milburga written by a Wenlock monk. In another manuscript dating to about 1200 (now at the British Library), the scribe dedicates the work to St Milburga and asks her to forgive his sins. This manuscript also contains a 15th-century poem in praise of the saint.

Many English monasteries celebrated feast days in St Milburga’s honour on 23 February and 25 June, the latter commemorating the rediscovery of her relics and their translation at Wenlock.

In January 1540, Wenlock fell victim to Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. Soon after, gold and silver plate from St Milburga’s shrine was sent to the king’s treasury in London. The fate of the saint’s relics is unknown.

Find out more

-

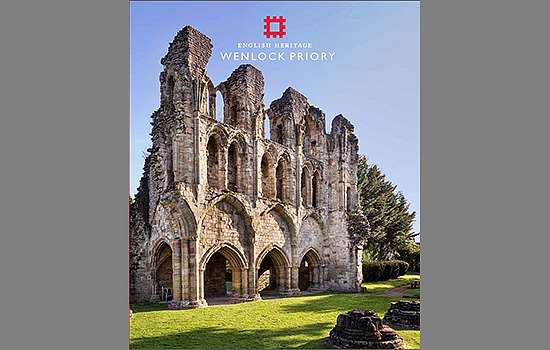

Visit Wenlock Priory

The impressive remains of the priory stand in a tranquil and picturesque setting on the fringe of beautiful Much Wenlock.

-

History of Wenlock Priory

Read more about the double monastery where Milburga presided as abbess, as well as the priory refounded soon after the Conquest on its site.

-

Buy the guidebook

This fully illustrated guidebook contains a comprehensive history of the priory as well as a complete tour of the impressive remains.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.