Romans: War

Roman Britain had the largest army of any of the provinces of the empire. Scotland and Ireland remained unconquered, and unrest on the northern frontier was a permanent problem, despite the strength with which Hadrian’s Wall was held.

LEGIONS AND AUXILIARIES

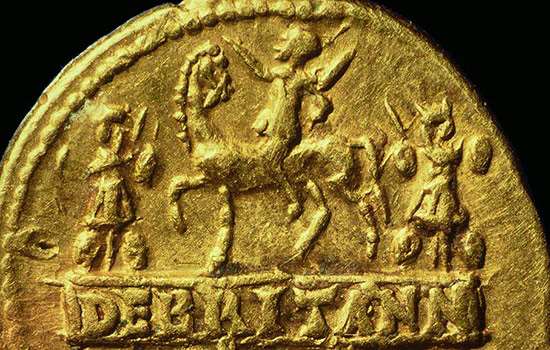

The Roman army of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD was divided into legions and auxiliaries. The legions were battalions of heavy infantry, all Roman citizens, some 6,000 strong. Auxiliaries were non-citizen units, originally recruited from the warrior peoples that Rome had encountered in her frontier wars. They were valued for qualities that the legions lacked, like expertise in mounted warfare.

Auxiliaries were organised into cohorts of infantry and alae of cavalry, and many mixed units – usually 500 strong. On Hadrian’s Wall, for example, there was a cohort of Tungrians (raised in Belgium) at Housesteads, an ala of Asturians (from Spain) at Chesters, and a cohort of Dacians (from Romania) at Birdoswald. Auxiliaries were also raised in Britain, but these units always served outside their home province.

Unlike the legions, auxiliaries were not commanded by individuals of senatorial rank, but usually by young men of the equestrian order. Such men would have risen through the imperial service and were used to an aristocratic way of life which they attempted to recreate as best they could in Britain.

FRONTIERS

Roman Britain also had one of the great fleets of the empire, the classis Britannica, formed to patrol the Channel. Last mentioned in the records in the AD 260s, it was based at Dover, where a Roman lighthouse still stands as a reminder of the importance of this port in the period. It’s now within the walls of Dover Castle.

After the consolidation of the conquest there was little military presence in the southern civil zone of the province. The army was permanently concentrated in the frontier zones in the north and west.

The bulk of the auxiliary army was stationed in smaller forts on Hadrian’s Wall or in the area immediately south of it. The legions were based far south of the Wall in fortresses at York, Chester and Caerleon (in south Wales), although there were bases for outlying detachments on the northern frontier, such as Corbridge.

Forts

Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall exemplifies the classic fort plan: a playing-card shaped rectangle, with a central range of buildings (the commanding officer’s house, headquarters and granaries) and barracks to the front and the rear. There are endless variations on this arrangement, however, and no two forts have identical plans.

Hadrian’s Wall and its forts were manned until the end of Roman Britain. From the 3rd century onwards, though, the fact that new kinds of fort were built along the south and east coasts of Britain shows that the prosperous south was increasingly threatened by raids from the sea.

Saxon Shore

These ‘Saxon Shore forts’ reveal a new style of military architecture to answer a new kind of threat. The first to be built, in the early 3rd century (such as Brancaster and Caister in Norfolk, and Reculver in Kent) were similar to the Hadrian’s Wall forts, with light defences and a neat rectangular shape. But the later forts built between about AD 275 and 300 have massive mortared walls, projecting towers and irregular circuits. There are immense surviving remains at Pevensey (East Sussex), Portchester (Hampshire) and Richborough (Kent).

Later still, after AD 370, there was an attempt to fortify the north-east coast south of Hadrian’s Wall with a series of small forts containing massive towers. Scarborough Castle in North Yorkshire contains the only visible example of these Yorkshire coast ‘signal stations’. Excavations have shown that the last garrisons of some of these posts were overwhelmed by attackers in the early 5th century.

Roman Stories

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

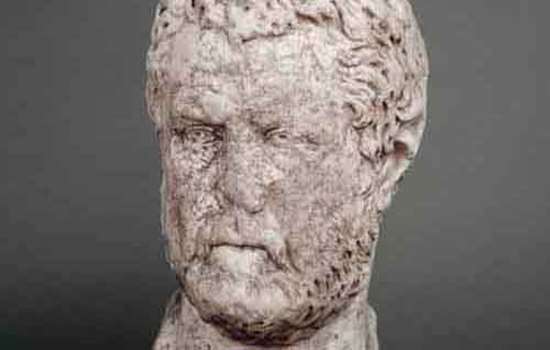

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.