Did you know that the 2017 Wonder Woman film was partly filmed at Tilbury Fort in Essex? (It’s a popular location to shoot at…)

In the movie, Wonder Woman leaves her home on Themyscira to help fight the First World War. The reality is she wasn't the only one; while they weren’t fighting in the trenches, many real women left the lives they knew behind in order to contribute to the war effort.

In this article, we’re taking a look at some of these remarkable women – the real wonder women of World War I.

Edith Cavell: Nurse and Martyr

Edith Cavell began her career in nursing in 1896 at the age of 30. In 1907 she moved to Brussels to help introduce modern nursing practices. Nurses then, as now, worked hard. Typically they were on duty for 12 hours at a time, with few holidays and very little time for life outside of work.

Detail of the Edith Cavell Memorial

In 1914, she was weeding her mother’s garden in Norfolk when she heard that Germany had invaded Belgium. She didn’t want to stay in England, saying “at a time like this I am more needed than ever”.

Cavell took charge of the St Gilles hospital, which became a centre of resistance to Belgium’s German occupiers. Allied soldiers were hidden in the building, provided with false papers and given help to escape into friendly territory.

But in October 1915, Cavell was arrested by the German army and court-martialled. She was found guilty of ‘assisting the enemy’, and executed by a firing squad at dawn on 12 October 1915.

She has a blue plaque at London Hospital, Whitechapel Road, and a memorial statue stands near the National Portrait Gallery. It’s inscribed with the words of forgiveness she spoke to the priest who visited her just before her death:

“Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

Dame Maud McCarthy: Inspirational Leader

Dame Maud McCarthy was the most senior nurse on the Western Front during the First World War. She sailed on the first ship to leave England with members of the British Expeditionary Force in August 1914 and was made Matron-in-Chief of the B.E.F. in France and Flanders.

Dame Maud McCarthy, Matron in Chief of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), in her office in the headquarters at Boulogne. Copyright: © IWM (Q 108193)

She began the war with 516 nurses in her charge, but by 1918 she had over 6,000. Nurses working at the front faced unprecedented challenges from the horrors of mechanised warfare, and dealt with injuries caused by shells, machine gun bullets, trench foot, gas attacks and land mines.

McCarthy was known for being an inspirational leader as well as a highly skilled administrator. She was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1918 and later given the Florence Nightingale Medal, which is the highest international distinction a nurse can receive. Her blue plaque is in Chelsea where she lived from November 1919 until shortly before her death in 1949.

Nan Herbert: Transformed Wrest Park

One of the first country houses to be offered for use in the war effort was Wrest Park in Bedfordshire. Nan Herbert, the resourceful and fiercely independent sister of its owner Auberon, was responsible for setting up and running the house as a hospital.

She became the matron of the hospital in February 1915, after an intensive course at Metropolitan Hospital in London. She assembled a team of 20 nurses who looked after the 1,600 soldiers that passed through the wards. Wrest Park became recognised as one of the best-run country house hospitals under her energetic leadership.

Nurse Ridley was one of the Wrest Park nurses with aristocratic background – she was the daughter of the Russian Ambassador, and a friend of Bron and Nan Herbert.

A fire ripped through Wrest Park in September 1916, and although all the patients were evacuated, it could no longer operate as a hospital. Bron was killed in action in November 1916. Nan inherited his titles. She married and sold Wrest Park in 1917.

Mary Macarthur: Workers' Rights Champion

After supplies of shells ran low in 1915, The Ministry of Munitions was founded and encouraged women to sign up to work in the factories. Nearly a million women were working in munitions factories by the end of the war. Known as ‘munitionettes’, Britain could not have fought the war without them.

Mary Macarthur speaking in Trafalgar Square about the boxmakers’ strike in August 1908 © TUC Library Collections at London Metropolitan University

Conditions were poor in the factories. Loud noise, long hours, short breaks and tough manual labour were one thing, but the women were at risk from harmful materials like poison gas, TNT and asbestos. Workplace accidents were common. In 1917, 73 people were killed and 400 injured at a factory in the East End of London.

To top it off, the munitionettes were paid less than their male counterparts. But one woman in particular tried to change that. Mary Macarthur campaigned tirelessly for workers rights and equal pay throughout her life. During the war she campaigned skilfully and forced the government to improve the wages and miserable conditions of the munitions factory workers.

You can find a blue plaque dedicated to Macarthur in Golders Green, north London.

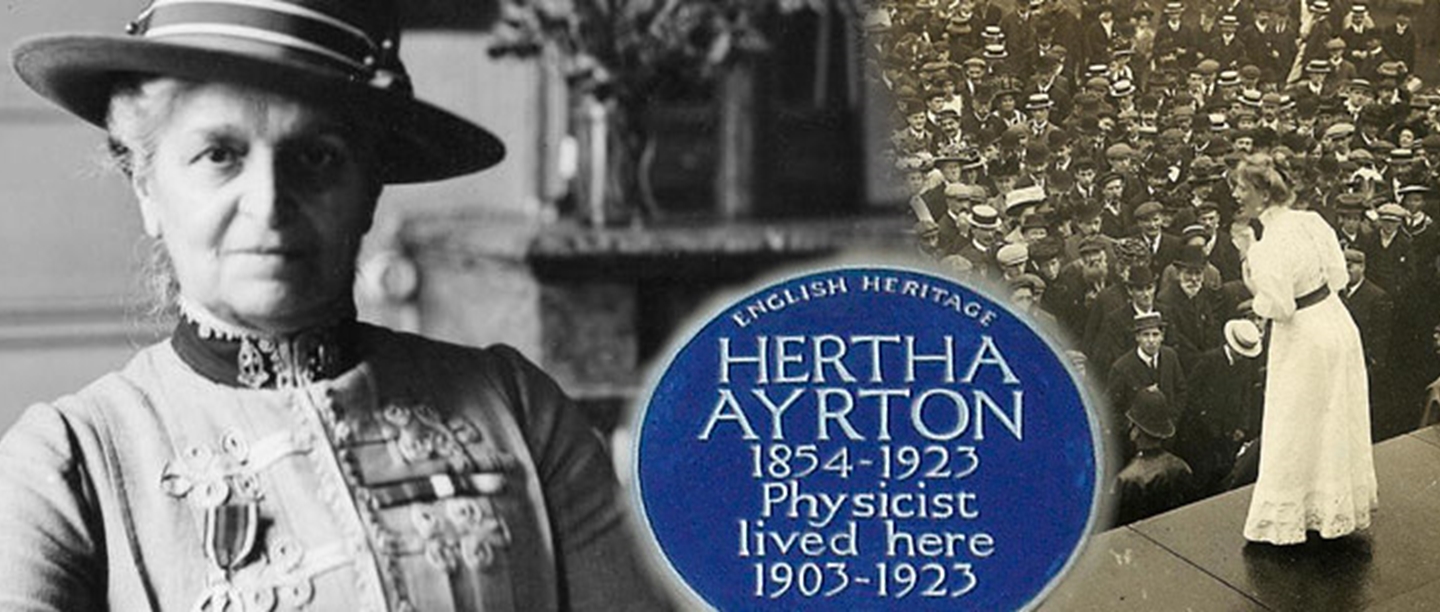

Hertha Ayrton: A life-saving inventor

Physicist Hertha Ayrton was one of the first female students to go to Cambridge University, and patented an engineering drawing instrument soon after she left in 1880. In 1902, despite doing important work in her field, the Royal Society rejected her election to its membership on the grounds that she was a woman.

During the war, she invented the Ayrton Fan, a device that helped soldiers clear poisonous gas from their trenches. Over 100,000 were issued to British troops and they were in constant use from May 1916 onwards.

A blue plaque to Hertha can be seen in Norfolk Square, Paddington. You can find out more about her groundbreaking work and support of women’s rights here.

The Ayrton anti-gas fan © IWM (FEQ 846) Fan made of waterproof canvas stiffened with cane, with a wooden handle. The blade has a semi-rigid centre, with loose end and side flaps. The fan is 107cm long, with a blade 41cm square and weighs less than 1lb.

Gertrude Bell: Linguist, diplomat and spy?

Born into the wealthy family that owned Mount Grace Priory in Yorkshire, Gertrude Bell had an extraordinary, inspiring life. She was the first woman to graduate from Oxford in with a first-class degree in Modern History, an accomplished mountaineer and a linguist.

Bell was drawn to the Middle East. She spent years immersing herself in the language, literature and archaeology of the region, and travelled widely. Soon after war broke out, she became part of the Arab Bureau, an intelligence operation that included TE Lawrence (‘of Arabia’) in its number.

By 1917 she was the oriental secretary to the British High Commissioner of Iraq, responsible for relations with the Arab population. She later helped to draw up the boundaries of Iraq and founded the Baghdad Archaeological Museum (today known as the National Museum of Iraq).

Sylvia Pankhurst: Pacifist

Pacifists and conscientious objectors (COs) did not have an easy time during the First World War. Men who refused to fight were more or less labelled as traitors. They were humiliated in the press and some were imprisoned at places like Richmond Castle – where the COs left some very moving graffiti. Obviously, the case was different for women who didn’t face conscription. But pacifism was still contentious, and for suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, holding anti-war beliefs meant the start of a lifelong rift with her family.

Miss Sylvia Pankhurst (C) being taken into custody by policemen during a women’s suffrage protest in Trafalgar Square. (Photo by Time Life Pictures/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia’s famous mother and sister, leaders of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) became ferociously pro-war. Sylvia became involved in the international women’s peace movement and, in London, focused her efforts on helping and organising working class women. She opened mother-and-baby clinics to help women whose partners were fighting in the war, or who had died. She used the newspaper of her Worker’s Suffrage Federation to give support to groups like the Non-Conscription Fellowship. In July 1917 it published Siegried Sasson’s anti-war letter, ‘Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration’.

Sylvia spent much of the rest of her life involved in socialism and anti-fascism, campaigning against the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in the 1930s and eventually settling in Addis Ababa.

There is a blue plaque to Sylvia in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea.

More to explore

-

Pioneering Women

Discover some of the figures in London’s history who took the historic first steps to open up new opportunities for women, and are commemorated by blue plaques.

-

THE HISTORY OF THE BISCUIT

Settle down with a cup of tea and treat yourself to the fascinating history behind the humble biscuit, from the Roman rusk to Victorian Petits Fours.

-

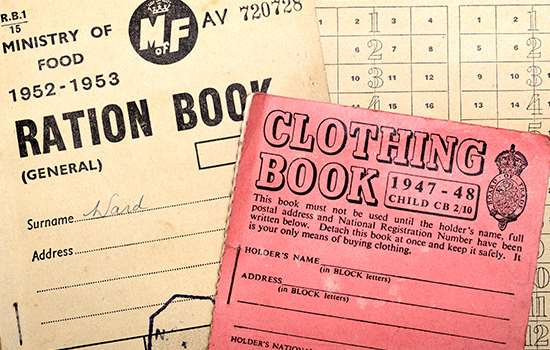

WWII: Wartime Wardrobes

Historian and author Julie Summers examines the impact of clothes rationing, one of the more memorable daily adjustments during the Second World War.