Last year we challenged our Members to write short ghost stories to coincide with the release of Eight Ghosts, a collection of haunting tales written by authors like Mark Haddon, Jeanette Winterson and Sarah Perry.

Now our Members have voted on the shortlist and Peter Malin’s, End of Days, was your favourite. Peter says he was inspired by a visit to Hurst Castle where he saw the eerie burnt orange sky, as a result of Hurricane Ophelia.

Read Peter’s winning story below and learn about the inspiration behind it with our short Q&A with the author himself.

We’d like to congratulate Peter on his winning entry and thank all of our entrants.

If you’re not a Member yet, you can find out more about joining us here. For as little as £3.75 a month you’ll be able to visit over 400 historic places and get access to offers and competitions like this one.

END OF DAYS, BY PETER MALIN

It was the strangest of days. A hazy, ochre light filled the air, as if the New Forest’s October leaves had squeezed all their yellows and golds into a sickly infusion. As the little ferry chugged steadily across the marina, weaving smoothly through the stilled yachts, it was possible to look directly at the sun, reduced by the day’s sulphurous veil to a bright copper disc.

For once, nobody spoke. Mary, usually so full of good cheer, looked as if she’d just received sad news. Even Kieron, the ferryman, seemed subdued, his attention focused on the squat outline of Hurst Castle ahead of them, flattened like an enormous crab on its raised promontory. Jack found the silence unnerving but didn’t want to be the one to break it.

The morning’s news had been full of speculation about the unusual atmospheric conditions, which had dimmed daylight and shrunk the spectrum to this eerie yellow filter. The internet was rife with end-of-days scenarios, substituting superstition for science. As they approached the castle, Jack felt increasingly anxious. He remembered the first time he’d come here, just after the war. He and his Aunt Emily had tramped along the spit from Milford on Sea, crunching the shingle into irregular hollows.

The castle was still occupied then, by a skeleton staff who kept it ticking over for a remobilisation that never materialised. As a local girl, Emily had performed here with Betty Hockey’s troupe of Nonstops, whose high-kicking routines had spiced up the wartime variety shows at the Garrison Theatre. Jack still had the framed sepia photograph of her, smiling at the theatre door. She wasn’t really his aunt; a city boy, he’d been evacuated to the New Forest to live with her family. They were all dead now; and he was old.

When the boat had moored at the wooden jetty, Jack let the others get off first, Mary with her bunch of rusty keys, ready to unlock the castle for the day’s visitors. None of them spoke; all seemed weighed down by the dreary light, curdling now into a syrupy gloom like the prelude to an eclipse. Perhaps the doomsayers were right after all.

Stepping on to the sallow turf, Jack felt uneasy; he was relieved, though, that at least he hadn’t been coughing this morning. It was Emily, he recalled, who’d given him his first cigarette. “See you later,” he said to Kieron, and added, “Strange day.” The ferryman barely glanced at him as he cast off and brought the boat round to return to Keyhaven. Jack loved this name: the place where the keys to the castle were cherished and kept safe.

When Jack retired, he’d moved back to Milford and offered his services as a volunteer at the castle. As resident handyman, he soon established himself as an indispensable part of the team. He steeped himself in the Castle’s characters and stories, which he would happily embroider for the benefit of visiting children. He particularly relished tales of the theatre, such as the moonless night when his aunt and her companions were almost stranded at the castle after drinks in the officers’ mess. They had to be carried out to their drifting boat by two or three soldiers in pitch darkness and thrown into it before it retreated on the receding tide.

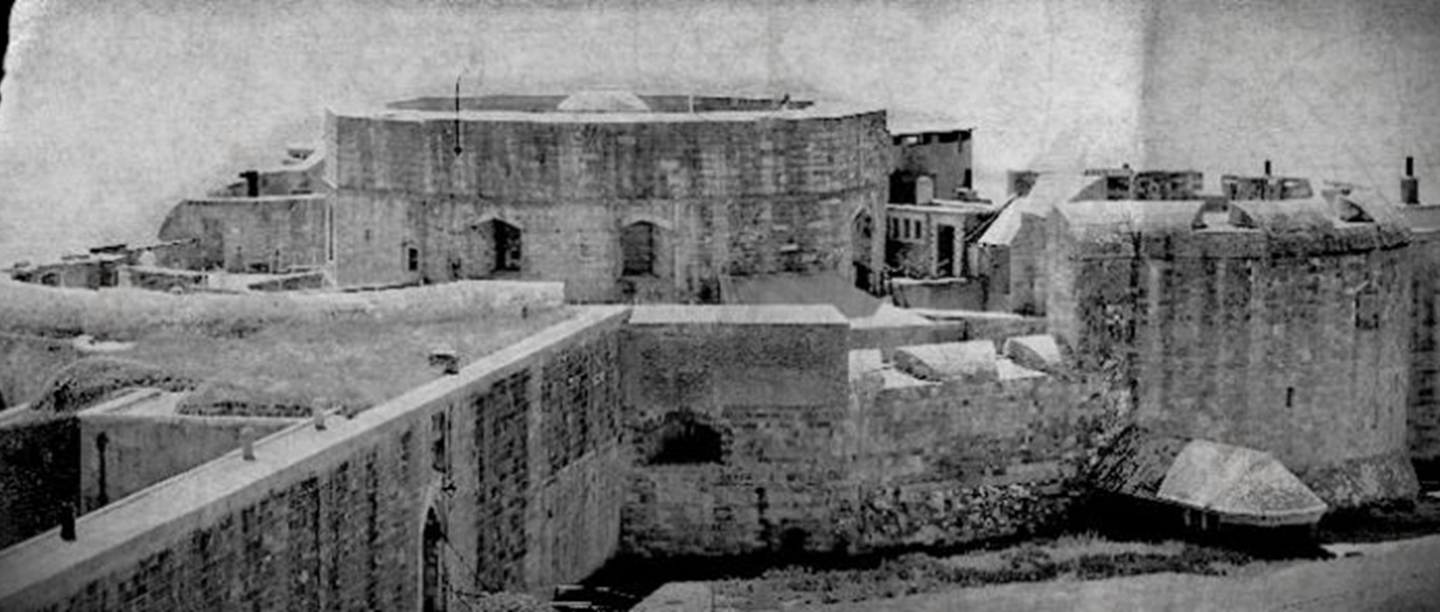

As Jack passed through the dark gateway into the grass-hummocked courtyard, he thought he heard voices whispering his name. This was not unusual; for ages now he had felt in tune with the spirits of those who had lived and died here. He began his day, as always, on the roof of Henry VIII’s circular fort, breathing in the spectacular view. Today, though, it was unearthly and disturbing under the sky’s thickening yellow, and he felt suddenly afraid. The castle’s Victorian extensions stretched out each way along the promontory, enclosing the bleak salt-marshes in the crab’s reaching pincers.

A little way along the shingle spit, a couple laboured towards the castle with a small child. The Isle of Wight was a formless haze, penetrated only by the regular blink of the Needles light. The upper air, turbulent now, twisted jaundiced leaves from far inland into a spinning vortex, shrill with the voices of the castle’s dead. And from the Garrison Theatre’s scooped-out cave of an auditorium, tucked away in the Victorian red-brick west wing, Jack could hear the sound of cheerful music and raucous laughter reverberating through the dense air.

Assuming the castle’s sound system had malfunctioned, Jack hurried down the spiralling stone steps back towards the theatre. This was where his aunt and her troupe had joked, sung and danced away the war, one night at a time, for hundreds of servicemen with no expectation of living longer than a few weeks. He could smell the acrid tang of packed bodies, the fug of cigarette smoke and stale beer, and as a thrill of fear trembled through his body, the air’s nicotine-stained fingers closed around him.

He was distracted by the arrival of the day’s first visitors, the family he’d seen negotiating the shingle bank. This, surely, would restore normality; he would entertain them with some of the castle’s livelier stories, like the Nonstops and their vanishing boat. The little girl ran towards him across the tussocky grass, as if she sensed he had tales to tell. He knew she was going to trip even before she went flying and sprawled headlong in front of him. He braced himself to catch her but, to his horror, she tumbled straight through him, as if she were merely an insubstantial projection of the sulphurous light.

The music rose into a head-spinning cacophony. The girl started crying as her parents rushed towards her and lifted her gently to her feet. Jack turned away, cursing his stupidity, understanding everything: for him, it was the end of days. At the theatre entrance, suffused in sepia twilight, Aunt Emily gave him a welcoming smile. Relaxing, he smiled back.

MEET THE WRITER: Q&A WITH PETER MALIN

What inspired you to write End of Days?

I drove down to the New Forest for a holiday in October 2017. It was the day the outer vortex of Hurricane Ophelia was blowing up dust from the Sahara and smoke particles from the wildfires in Portugal. This resulted in the south of England being cast into a yellowish gloom. When I visited Hurst Castle on the following day, the light was still opaque and eerie, and I knew I had the background atmosphere for my story.

What impressed you most about Hurst Castle?

This was my one and only visit to Hurst Castle. I arrived there on the little ferry, along with some of the staff and volunteers who were about to open it up for the day. The castle’s setting is utterly unique, on a bleak promontory at the end of a long, shingle spit reaching out into the Solent. I was particularly struck with how the castle’s 19th-century extensions stretch out like arms on either side of Henry VIII’s circular fort, enclosing the lagoon, marina and salt marshes in an ominous embrace.

How did visiting Hurst Castle help you create your characters?

At first I thought the ghosts in my story would be those of two people who had been imprisoned in the castle; Charles I and Father Paul Atkinson. Charles I was confined at Hurst Castle for nearly three weeks in 1648 before being moved to London for trial and Atkinson was a Franciscan friar who died there in 1729 after 30 years’ incarceration.

When I came across the Garrison Theatre, however, with its cramped, chilly, claustrophobic auditorium, I knew that this would be the focal point of the story. This was inevitable, I suppose, given my theatrical interests. The tales of Betty Hockey and her concert party entertaining the troops during World War Two provided the perfect inspiration.

What was the process of writing your story for our Members’ ghost story writing competition?

I drafted the story, which went through four versions, while I was still on holiday staying in Lyndhurst. As it wasn’t practical to return to the castle, I was glad to have bought the guidebook to remind me of its key features. Getting the story down to just under 1000 words was a struggle, and I was sorry to lose many details of character and setting from the earlier drafts. What I think makes a successful ghost story is atmosphere rather than shocks – but it all depends on the particular story you’re telling.

What do you most enjoy about being a Member of English Heritage?

I’ve been a Member of English Heritage for many years. Not only does my membership give me access to many fascinating places, but it means I can return to them again and again – often just for tea and cakes! I’m particularly intrigued by the different layers of history within a single place, lying one on another like geological strata. History is intrinsically interesting, of course, but it also offers us lessons, even warnings, about the world as it is now. I’ve just been reading The Way the World Is Going, a collection of H. G. Wells’s articles and lectures from the late 1920s, and I could have been reading about the state of the world in 2018. Much more terrifying than any ghost story.

VISIT HURST CASTLE

Hurst Castle was built by Henry VIII in the 16th century to guard the Needles Passage – the narrow western entrance between the Isle of Wight and the mainland. During this time it was one of the most advanced artillery fortresses in England. In the 17th century, the castle was used as a prison for eminent captives. The castle was in use up until the Second World War.

Last year we invested £1 million to conserve the site for future generations to enjoy.

Hurst Castle is currently closed over the winter and will reopen in the spring. Visit our website for the latest information on opening times.

ABOUT EIGHT GHOSTS

Eight Ghosts is a book of new spine-tingling tales written by eight award-winning contemporary authors and inspired by our historic places. Authors include Mark Haddon, Sarah Perry, Jeanette Winterson, Max Porter, Andrew Michael Hurley, Stuart Evers, Kate Clanchy and Kamila Shamsie.

In an English Heritage first, we challenged the writers to visit our sites and create original fiction based on their experience. The book also features a chapter by author and journalist Andrew Martin on our historic places and their supernatural legacies.

You can buy the book from our online shop.

BECOME AN ENGLISH HERITAGE MEMBER TODAY

Membership gives you unlimited access to over 400 historic places for a whole year. Stand in the places history happened and enjoy a fun day out for you and the whole family. As a Member you’ll receive a Members’ magazine and handbook, invitations to hundreds of historical events and discounts for other attractions.

For more information and to join as an English Heritage Member, visit our website.