A Glorious Beginning

In 1539, Henry VIII’s preparations for war included a huge construction programme of new artillery forts on the south and east coasts of England.[1] Three castles were to protect the vulnerable beaches around Deal and the Downs, an important naval offshore anchorage. These castles were a response to an invasion threat that resulted from Henry VIII’s foreign policy, particularly his involvement in the struggle between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (reigned 1516–56), and Francis I, King of France (r.1515–47). By 1539, Henry’s conduct in his divorce from Catherine of Aragon, in the destruction of monasteries and in taking control of the Church in England, had resulted in their alliance against him, urged on by an enraged Pope.

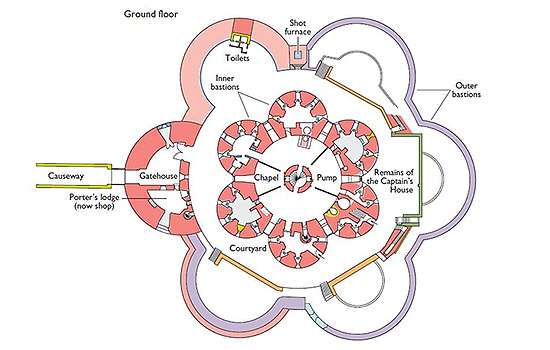

The Downs castles were completed in October 1540,[2] and by the end of Henry’s reign in 1547 Deal was one of 42 new artillery forts that protected ports, anchorages and estuaries. Those built in the first few years, including Deal, adopted a form that enabled all-round defence, and were planned and built by the staff of Henry’s Works departments.[3] They are beautiful architectural designs, intricately and scientifically planned to concentrate the fire of heavy guns against ships, while also enabling close defence against a land force. Deal Castle had guns mounted in five tiers.

In 1547 Deal was armed with 57 guns,[4] but Henry’s grand military vision did not survive his death in that year, and a castle fully armed and bristling with over 140 guns was never realised. For the remainder of the 16th century, the castle was maintained on a shoestring and fully prepared only in response to invasion scares in 1568–70, 1583–8 (including the Armada of 1588) and 1596–9. In 1570 the castle had only 17 guns, most of them unserviceable, making all-round defence unachievable.

Stuart Neglect

James I (r.1603–25) and Charles I (r.1625–49) neglected the castle. However, a small garrison of about 22 men did their best to protect the Downs, where disputes between ships of rival nations often erupted into fighting, and where pirate vessels regularly preyed on merchant ships.

Keeping the peace was often impossible. In 1639, during the Battle of the Downs, the guns of Walmer, Deal and Sandown could not prevent a Spanish fleet, which was seeking the neutrality of the anchorage, from being mauled by a Dutch fleet. Several Spanish vessels were sunk and 2,000 shipwrecked sailors struggled ashore, leaving the English to organise their relief.

Read more about The Battle of the Downs

War comes to the castle

Though peaceful throughout the First English Civil War (1642–6), Deal was caught up in war in 1648.[5] Infighting between rival Parliamentary factions over the future of Charles I resulted in a mutiny of the fleet in the Downs. The garrisons of the castles at Deal, Walmer and Sandown defected in favour of the king and Parliament sent a force to retake them, under Colonel Nathaniel Rich, which arrived early in June.

Walmer succumbed to a murderous mortar bombardment in July, and although Deal received similar treatment, it held out. On 15 August, a relief force attempting to break the siege and resupply the castle was decisively defeated. The defenders had to surrender, on 25 August, followed by Sandown on 3 September. Parliament had won, and five months later Charles I was executed.

Read more about walmer castle’s history

Deal and England at war

During the Commonwealth (1649–60) and after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, England fought against the Dutch (1652–4, 1665–7 and 1682–4) and the French (1688–97). The English coast was often threatened and the Downs anchorage was always a target.

In 1667 a Dutch fleet cruised the Kent coast, seeking an opportunity to attack. The captain of Deal Castle, Colonel Silius Titus (1622/3–1704), prepared defences in anticipation of a landing between Walmer and the Isle of Thanet. He commanded several hundred soldiers comprising all the castle garrisons, local trained bands and several companies of professional soldiers, including the newly formed Duke of York and Albany’s Maritime Regiment of Foot (today’s Royal Marines). In the event, the Dutch attacked the river Medway, and Deal was left unscathed.

Fortress and residence?

In 1713 British involvement in the War of the Spanish Succession, which had engulfed Europe since 1701, came to an end. Peace prompted a review of coastal fortifications which, at Deal, resulted in modernisation.

Military engineers from the Ordnance Office installed 12 modern 9-pounder guns. In 1730–32 they built the Captain’s House and improved a large garden for him just outside the castle. Craftsmen demolished the old Tudor parapets, replacing them with the more decorative crenellations that survive in part today. Subsequent alterations included new parapets for the three seaward-facing bastions to enable a wide arc of fire for each gun (1738); a new keep roof (1739); a new drawbridge (1741); and a high brick wall to enclose the captain’s garden (1744–50).

The result of all this work was an uneasy hybrid – a larger, more fashionable residence for the captain and a reformed battery of guns to defend the Downs. By this date only a lieutenant, a master gunner and a porter were usually based in the castle. In 1749 the lieutenant was also the master gunner, who looked after the guns and stores. In 1765, a tiny cabin in the courtyard provided shelter for a duty gunner to rest and sleep in; the other gunners were sent for when needed. The whole of the keep and inner bastions formed the captain’s accommodation.

In 1773 a muster listed a nominal garrison of only eight gunners, enough for only two guns. During major alarms, as occurred in 1744–5 and 1779 when French forces were expected, militia and regular soldiers came to help the gunners operate the guns and defend the castle.

The french revolutionary and napoleonic wars

During Britain’s long conflict with France between 1792 and 1815, the British government devoted its resources to fighting a global war. The south-east of England, vulnerable to French invasion, became a huge military zone. Deal Castle was compromised defensively by the Captain’s House, and although the bastions still mounted guns that would be useful against ships, it was no longer considered a key defence.

However, its symbolic importance was considerable, being the residence of the captain, an eminent member of society who took a lead in the local volunteer defence effort. Deal town and the village of Walmer accommodated a military and naval garrison in huge new barracks built in 1794–7 for about 1,000 men. A naval hospital was added in 1800 to serve a Channel squadron of the Royal Navy, with the Navy Yard at Deal as its supply depot.

Several large expeditions began at Deal, including the attack on Walcheren in the Netherlands in 1809, an attempt to stop French use of the port of Antwerp. Deal was one of five ports of embarkation for a force of 40,000 men. Unfortunately the expedition failed and thousands of soldiers died of ‘marsh fever’ (malaria), which filled Deal hospital to overflowing.

Deal by the sea

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Deal remained a military and naval town and the castle continued as the captain’s residence. Robert Smith, Lord Carrington, the last captain to be salaried, remained in post until his death in 1838. Subsequently, the captaincy was awarded for service to the state and used by most captains as an occasional retreat, as Deal became an attractive seaside resort in summer.

By 1860 small ornamental gardens took up parts of the outer bastions, cheek-by-jowl with four 32-pounder guns whose presence was nothing more than a memory of the past (they are still at the castle). Across the Deal–Walmer road, walls enclosed a large, productive kitchen garden with a conservatory and a hot bed for forcing plants, and, against its outer face, the captain’s stable and coach house.

Yet, even in the face of this genteel residential character, the Office of Ordnance continued to maintain the four guns and a gunpowder magazine in the castle. In reality, these guns were obsolete relics and no one considered the castle as a place of defence.

Modern times – and war again

In 1904 the War Office transferred the castle to the Office of Works, to be conserved as a historic building. But it was still the captain’s residence and there was often a strained ‘landlord and tenant’ relationship, with disagreements over what could be provided from the public purse. Nevertheless, maintenance continued until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and resumed when the war ended.

In May 1940, with a German invasion expected, the Royal Artillery requisitioned the castle, and built two emplacements for 6-inch guns next to the promenade and an underground magazine in the castle’s paddock. They built a concrete observation post, to direct the guns, on the east bastion, while the castle interior became battery HQ. Engineers erected barbed wire and concrete obstacles (‘dragon’s teeth’) on the beach, promenade and adjacent streets, to hinder the movement of enemy forces that might land. In April 1944, as the prospect of invasion receded, the Home Guard replaced most of the artillerymen until the end of the war. The most significant wartime moment was when a German bomb, falling on 5 October 1940, severely damaged the Captain’s House.

In 1945 the Office of Works resumed responsibility for the castle, and made plans to restore it and open it to the public, as closely as possible to its Tudor form. This involved removing the remains of the Captain’s House, and from 1951 until 1974 no captain was appointed. The castle reopened to the public in the early 1960s. Today, the castle retains a link with the Royal Marines, whose Commandant General holds the captaincy as an honorary position, though the castle is no longer a residence.

Find out more

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan to discover how Deal Castle developed over time.

-

The battle of the downs

Read how a major sea battle between the Dutch and the Spanish, in full view of Deal Castle, revealed as much about the English navy as it did about its participants.

-

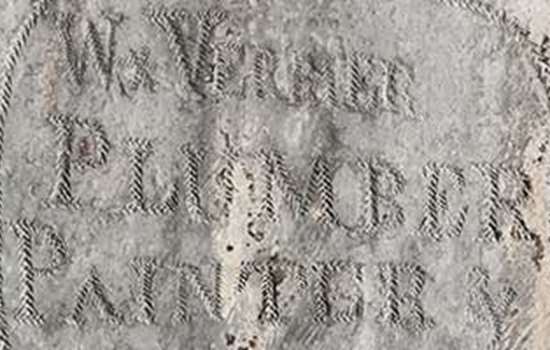

Deal graffiti

Since at least 1724, people have left their marks at Deal in the form of graffiti scratched into the castle’s roof. View a gallery of the graffiti.

-

History of Walmer Castle

Walmer, together with its neighbour Deal Castle, and the now largely vanished Sandown Castle, formed a chain of coastal artillery forts designed to control the Downs.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.