Shifting Perspectives

Today we take it as given that important monuments, which attest to the nation’s history, should be protected and accessible to the public. But this was not always the case. Many monuments, now open to the public, were originally in private hands.

It was towards the end of the 19th century that attitudes began to change. The Ancient Monument Protection Act of 1882 was passed, which encouraged those who owned significant historic sites (although initially only prehistoric sites) to hand them over to the guardianship of the state. Once placed in guardianship, the government – through the Office of Works – would take on any financial responsibility for the monument.

Impact of the 20th Century

Attitudes towards heritage continued to evolve in the 20th century. This was a time of tremendous political, cultural and social change, punctuated by the catastrophe of the First World War. The old political order was questioned, and new government initiatives, like the 1909 ‘Peoples Budget’, which targeted the lands and incomes of the wealthiest to fund social reforms, emerged.

It was in this cultural landscape that the 1913 Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act was passed. This gave the Office of Works new rights to place protective measures on any monument they deemed worthy of protection, with or without the owner’s consent. Sites of national historic importance were no longer something left to the fortunes of individuals.

The Guardianship of Rievaulx Abbey

Rievaulx is perhaps the most beautiful of our ruined abbeys and its permanent preservation is a work which would meet with everyone’s approval.

(Charles Peers)

Rievaulx Abbey, located on the Duncombe estate, was one of the Office of Works’ earliest acquisitions. It came to the attention of Charles Peers, the Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments, in the early 1900s and in 1912 he made his first official visit to the site.

Peers was determined to protect and preserve sites like Rievaulx. Where others could only advise and cajole, with the passing of the 1913 Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act, Peers could exert real pressure.

Negotiations to take on responsibility for the abbey were halted by the outbreak of war in 1914. But on 20 July 1917, following the death of the estate owner, Lord Feversham, at the Somme, Rievaulx was officially transferred into the guardianship of the Office of Works.

A New Aesthetic

The decayed monastery, which before treatment is generally the most meaningless jumble, regains the orderliness that was, in fact, the keynote and background of the Rule.

(Edmund Vale, 1939)

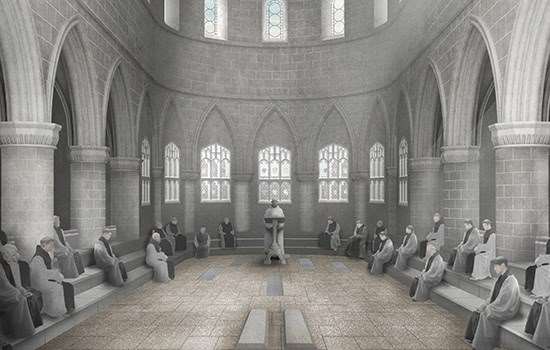

Since the monastery was dissolved in 1538, soil and rubble had settled over its ruins and its ivy-clad walls had come to characterise its crumbling silhouette. But as part of the representation of the abbey, the Office of Works commissioned the vegetation to be stripped from the walls and 90,000 tonnes of debris to be cleared away. The outline of the cloisters and church slowly became visible in the grass for the first time, revealing the original plan of the medieval monastery.

The intention behind this work at Rievaulx was to move away from the romantic to the instructive presentation of buildings – to enable a monument to be read like a manuscript or map.

Excavating Rievaulx

The clearance work at Rievaulx was not carried out by archaeologists, but by a team of local workmen. Many of them were returning from the battlefields of the First World War. Their role was to consolidate the ruins and clear the site of spoil.

Over the course of 20 years 120 men worked on the site, some returning repeatedly while others were retained full-time. For some, the conservation of Rievaulx became their life’s work.

The employment record and wages book from 1919 to 1947 still survives, allowing biographies of some of the men to be explored. Among the men who contributed to clearing and consolidating the ruins at Rievaulx are:

John Weatherill, mason (1881–1960)

John was a local man who lived in Rievaulx village with his wife and family. He had come from generations of masons and began his career as an apprentice mason with the Duncombe Estate aged 14. After military service, Weatherill returned in 1919 to employment with the estate, transferring shortly after to the Office of Works. In 1950 he was one of the founders of Helmsley Archaeological and History Society and a major contributor to its book History of Helmsley, Rievaulx and District.

Amos Dickinson, scaffolder (1883–1927)

Born in Scarborough, Amos worked as a general labourer and gardener before enlisting in the Northumberland Fusiliers. He was employed at Rievaulx from 1919 to 1926 and was the main scaffolder.

Robert (Bob) Cornforth, labourer (1894–1971)

Born locally in Hawnby, before the war Bob worked for his widowed mother. After demobilisation he was first employed at Rievaulx in 1920, lodging weekly in Rievaulx before his marriage. He eventually served most of his adult working life for the Ministry of Works at Rievaulx Abbey and Byland Abbey and was awarded a Civil Service medal.

A Hidden Collection

During the work at Rievaulx over 10,000 finds were recovered, ranging from personal possessions, coins, ceramic vessels and window glass to architectural stone and sculpture.

A system was devised – and meticulously kept by the site foreman, Mr Duncanson, until 1927 – which mapped where each find had come from. It also ensured every object was labelled with its find number and context. Wooden work sheds were constructed east of the abbey church, one of which became the site’s first museum.

Read More

-

History of Rievaulx Abbey

Discover the history of Rievaulx Abbey, from its foundation in 1132 to its 20th-century preservation.

-

Rievaulx Abbey Collection

Explore a selection of objects that give a unique insight into the workings of the medieval abbey.

-

Why does Rievaulx Matter?

Discover why Rievaulx has been considered both architecturally and historically significant since the 12th century.