London Statues Gallery

English Heritage is responsible for maintaining a number of the capital’s public statues. The majority of these can be found in areas of Westminster such as Whitehall, Charing Cross and St James’s.

The statues represent various individuals throughout British history including monarchs, from Charles I to Edward VII, nursing heroes Edith Cavell and Florence Nightingale, and explorers Sir John Franklin and Captain Scott.

In this gallery you can explore all 39 London statues in our care. As we continue our research, we look forward to updating these pages with more details on each statue – delving further into their history and design, and learning more about the individuals they commemorate. Come back soon for more information.

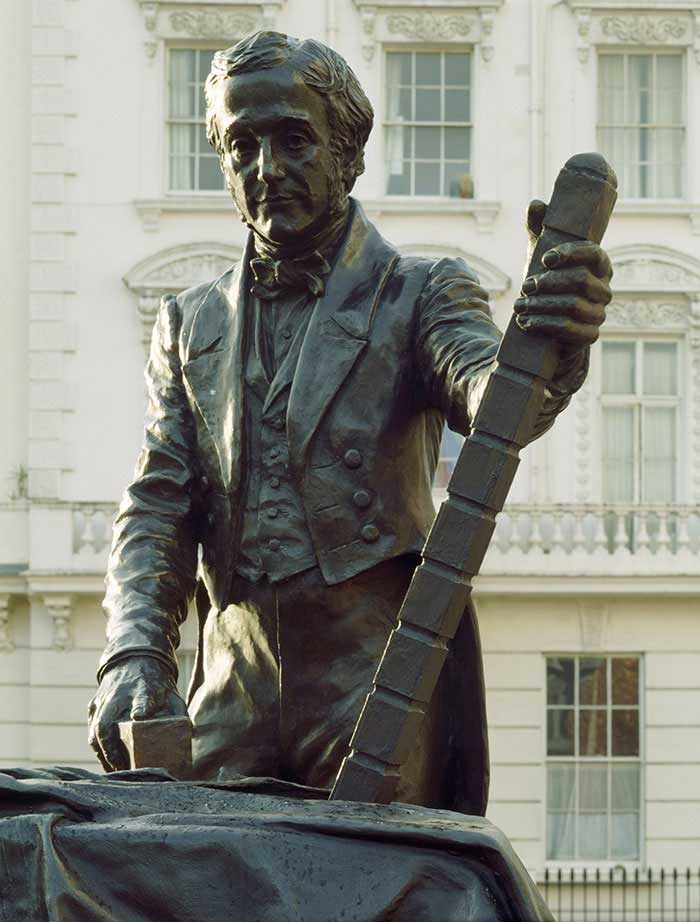

Captain Scott

Waterloo Place, St James’s

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (1868–1912), known as ‘Scott of the Antarctic’, was a Royal Navy officer and explorer, best known for the Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole (1910–13) that cost him his life. Scott’s party reached the Pole on 17 January 1912, shortly after a Norwegian expedition led by Roald Amundsen had done so.

Scott also led an earlier Antarctic expedition, the Discovery expedition (1901–4), that ventured further south than anyone previously.

The bronze statue, funded by a naval officers’ subscription, is by Scott’s widow Kathleen (1878–1947), and was unveiled in her presence on 5 November 1915.

The inscription on its accompanying plaque names the other four members of Scott’s final expedition – Wilson, Bowers, Oates and Evans – and features a quotation from his diary. An identical statue carved in marble stands in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Read more on Captain Scott

Christopher Columbus

Belgrave Square, Belgravia

Italian explorer, Christopher Columbus completed four voyages across the uncharted Atlantic Ocean, paving the way for European colonisation of the Americas. His legacy is marred by his brutal treatment of native populations in the Caribbean and the devastating effects of colonisation for them.

His first and second voyages (1492 and 1493) explored the Bahamas and the Caribbean, and established colonies in Hispaniola and Cuba, where Columbus was appointed Viceroy. He was recalled in disgrace after his third voyage (1498–9), accused of tyrannical treatment of the islands’ inhabitants. He was later restored to royal favour and made a fourth voyage to the Caribbean in 1504.

The life-size bronze statue by Tomás Bañuelos was presented to the United Kingdom by the Spanish government in 1992 to mark the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage.

Image: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Read more on statues and the history of empire

Duke of Devonshire

Whitehall, Westminster

Spencer Compton Cavendish (1833–1908), the 8th Duke of Devonshire, was born into one of the richest aristocratic families in Britain. He sat in the House of Commons (1857–91) and was offered, but refused, the premiership three times.

Devonshire’s most important actions were politically contentious: he led the breakaway Liberal Unionists, who left Gladstone’s Liberal Party over the issue of Irish Home Rule in 1885 and opposed it again in 1893. This arguably contributed to Ireland’s eventual departure from the United Kingdom and the formation of the Irish Free State, now the Irish Republic: the opposite result to what the Liberal Unionists intended.

The statue by Herbert Hampton is at the junction of Whitehall and Horse Guards Avenue at one end of the Banqueting House. It was unveiled in 1911.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

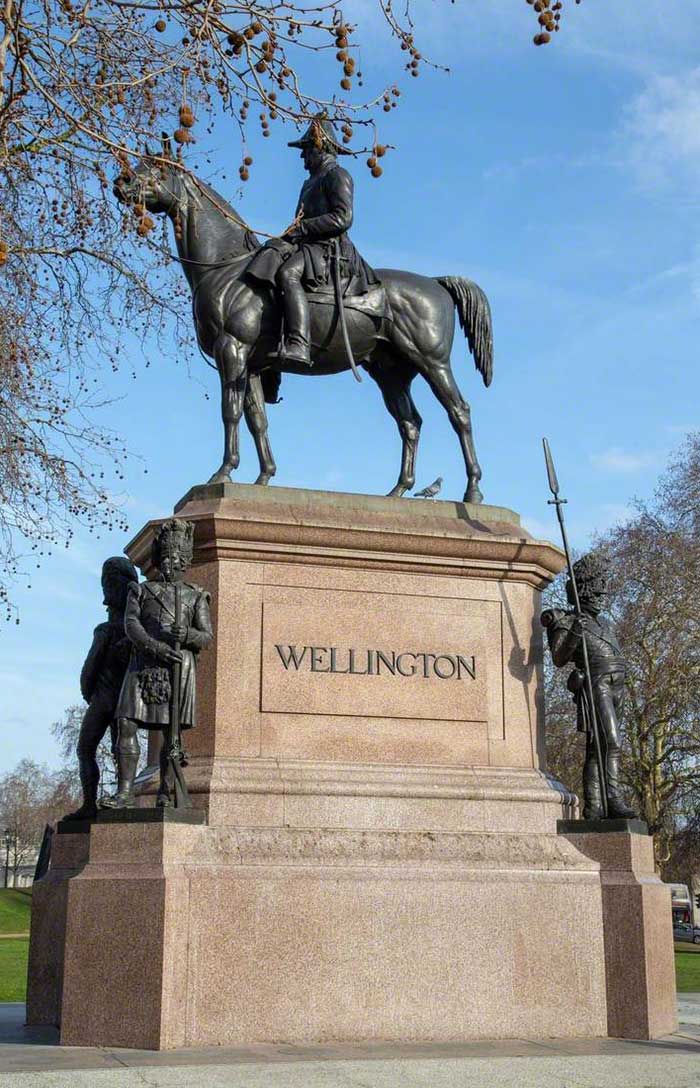

Duke of Wellington

Hyde Park Corner, Westminster

The 1st Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852), led the allied army to victory against Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo (1815), ending the Napoleonic Wars. He later served as prime minister in 1828–30 and for a shorter period in 1834.

The bronze statue of Wellington shows him seated on his famous horse, Copenhagen. The plinth is made of pink granite, decorated at each corner with representatives of the British army: a Grenadier, a Scottish Highlander, an Irish Dragoon and a Welsh Fusilier.

The statue, by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm, was unveiled in 1888 and faces Apsley House, Wellington’s London home. It replaced an earlier one by Matthew Coates Wyatt which had originally surmounted the nearby Wellington Arch.

Dwight D Eisenhower

Grosvenor Square, Mayfair (currently in store)

Dwight David Eisenhower (1890–1969) was President of the United States from 1953–61. His presidency saw the US at the peak of its international prestige and influence. Though much of his attention was engaged by foreign policy, his administration saw the continuation of Democratic policies such as Social Services, highway building, racial desegregation of the armed forces, and the early stages of the establishment of Civil Rights for African Americans.

The statue, by Robert Dean, was presented to the British people by the citizens of Kansas City in 1989 to commemorate the service of Charles H. Price II, the US Ambassador to the United Kingdom (1983–9), and his wife, Carol Swanson Price. It stood at the north-west corner of Grosvenor Square, close to the then US Embassy, but is currently in store during the redevelopment of this site.

Earl Haig

Whitehall, Westminster

Field Marshal Douglas Haig (1861–1928) was Commander-in-Chief of the British Army on the Western Front during the First World War, including battles at the Somme (1916), Passchendaele (1917) and the Hundred Days Offensive (1918).

His contribution to an Allied victory is beyond doubt, but some believe that this was at too high a cost in his soldiers’ lives. Others claim it was the need to break the strategic stalemate on all sides that caused so many casualties.

After the war, Haig campaigned for soldiers’ welfare and was instrumental in creating the British Legion, which is still active today.

Haig’s statue was commissioned by Parliament in 1929 from Alfred Frank Hardiman, and was unveiled in 1937.

Read more on London war memorials

Edith Cavell

St Martin’s Place, Charing Cross

Edith Cavell (1865–1915) was a British nurse who was executed for helping allied soldiers to flee German-occupied Belgium during the First World War.

Cavell was matron of the Birkandael Medical Institute in Brussels from 1907, from where she assisted around 200 allied soldiers to escape via the Netherlands

Convicted of ‘war treason’ under German Military Code and executed in 1915, Cavell was widely seen as a martyr, and her death was used as propaganda for British military recruitment.

The marble statue and its granite setting, unveiled in March 1920, are by Sir George Frampton. Cavell’s words to a priest on the eve of her execution were later added to its plinth at the request of the general public: ‘‘Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.’’

Read more

Florence Nightingale

Waterloo Place, St James’s

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) is famed for the life-saving improvements in cleanliness and hygiene she promoted in field hospitals during the Crimean War (1854–6), and for her contributions to public health and good nursing practice in general.

In 1860 she founded the Nightingale School and Home for nurse training at St Thomas's Hospital, London.

The statue, funded by public subscription and completed in 1915 by Arthur George Walker (1861–1939), shows Nightingale as ‘the Lady with the Lamp’ so named from her nightly inspection rounds in the Crimea.

Close by is the Guards Crimean War Memorial and the statue of Sidney Herbert, who was Secretary of War during the conflict.

Read more

“George II”

Golden Square, Soho

The statue is said to represent George II, King of Great Britain and Ireland, and elector of Hanover. During his long reign (1727–60) George II left domestic politics largely to politicians and exercised his influence more in foreign policy. He was strongly opposed to France and supported British involvement in the War of Austrian Succession (1740–48) and the Seven Years War (1756–63).

The stone statue represents a man in Roman military dress and was erected in Golden Square by an anonymous donor in 1753. It is thought to be by the sculptor John Nost and may have come from the 1747 demolition sale of Cannons, a Baroque house in Stanmore, Middlesex. However, there remain questions over its provenance and identification as George II.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Charles De Gaulle

Carlton Gardens, St James’s

French Army officer, Charles de Gaulle (1890–1970) led the Free French forces during the Second World War, and later became President of France (1959–69).

Based at Carlton Gardens, London, where there is also a blue plaque, de Gaulle headed a government in exile after the fall of France in 1940. After liberation, he led the provisional government until 1946.

As President of France, de Gaulle twice vetoed British entry into the European Economic Community (EEC).

The statue, by Angela Conner, was unveiled in June 1993 by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. Leading the campaign for de Gaulle’s commemoration was Lady Soames, the daughter of Winston Churchill.

Read more on Charles de Gaulle

Charles Gordon

Victoria Embankment Gardens, Charing Cross

Major-General Charles George Gordon (1833–85) gained a military reputation in command of a Chinese imperial army in 1860–64 during the Taiping Civil War. In 1885, as Governor of the Sudan during the Mahdist War, Gordon was killed at Khartoum during an uprising against Ottoman-Egyptian rule.

Popularly hailed a hero, Gordon was principled and courageous (he tried to end slavery in the Sudan), but politically reckless. His defence of Khartoum defied the British government, which had no interest in a permanent takeover in the Sudan.

Gordon’s statue, by Sir William Hamo Thornycroft, was unveiled in Trafalgar Square in 1888. It was moved into storage at Mentmore, Buckinghamshire, in 1943 and re-erected at its current site in 1953.

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery

Whitehall, Westminster

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery (1887–1976) led the Second World War victory at El Alamein, Egypt (1942), a battle that was widely regarded as a turning point in the war. He was also the senior British commander for the D-Day landings (1944) and went on to be Chief of the Imperial General Staff (1946–8).

‘Monty’ was popular with the ranks, partly from his concern to limit casualties. His lack of tact and brusque manner alienated many of his colleagues and superiors, but his abilities as an army commander were generally acknowledged.

The statue, by Oscar Nemon, shows Montgomery wearing his distinctive army beret, and was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in June 1980.

Read more on Montgomery

George Washington

Trafalgar Square, Westminster

George Washington (1732–99) was the first president and one of the founding fathers of the United States of America.

Washington commanded the continental army to victory in the American War of Independence. He presided over the 1787 Constitutional Convention, and served as President from 1789 to 1797, the first holder of the office.

Washington owned several hundred enslaved workers at his Virginia estate, and was cautious about emancipation, as this was a divisive issue among the states of the new Union. They were freed by his widow in 1801.

The statue is a bronze replica of a marble statue in Richmond, Virginia by Jean-Antoine Houdon, c.1785. It was presented by the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1921.

Read more on statues and the History of Empire

José de San Martín

Belgrave Square, Belgravia

General José de San Martín (1778–1850) played a large part in winning independence from Spain for Argentina, Chile and Peru during the 1810s.

After fighting on the Spanish side in the Napoleonic wars, the Argentine-born San Martín first secured self-determination for his home country, and then helped to do the same for Chile and Peru.

For a time he was effectively the ruler of Peru, but he resigned power in 1822, and spent the rest of life in exile, notably in London and Paris.

The bronze statue, by the Argentinian Juan Carlos Ferraro, was a gift to London from the British community in Argentina. The Duke of Edinburgh unveiled it in November 1994.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

King Charles I

Trafalgar Square, Westminster

Charles I (1600–49), son of James VI of Scotland and I of England, succeeded his father as King of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1625. His reign was marked by divisions mainly caused by his belief in his divinely ordained right to rule and attempt to rule without Parliament. This led to the English Civil Wars (1642–50) where the Royalist cause was eventually defeated. Charles was found guilty for making war on his people and was executed in January 1649.

The equestrian statue by the French sculptor Hubert le Sueur is London’s oldest bronze statue and one of the most historically significant public artworks in Britain. It was originally made for the garden of the Lord Treasurer’s house at Roehampton (c.1630–33). In 1649 Parliament ordered it be melted down but the statue was kept hidden. After the Restoration of the monarchy (1660) it reappeared and was erected at its current site.

Read more

King George III

Cockspur Street, St James’s

George III (1738–1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 1760, and King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1801. His long reign witnessed the key stages of the Agricultural Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, the loss of Britain’s North American colonies, the expansion of British colonial possessions elsewhere, the Act of Union with Ireland, and Britain’s ultimate victory in its 23-year conflict with France (c.1793–1815). It saw the transatlantic slave trade reach its height, but it also saw the triumph of the campaign to abolish the trade in 1807. King George himself consistently opposed abolition.

The statue of George III, on his horse Adonis, was the first statue of a monarch to be paid for by public subscription. Made by Matthew Cotes Wyatt, it was unveiled in 1836.

King Edward VII

Waterloo Place, St James’s

Prince Albert Edward (1841–1910) was born at Buckingham Palace, the eldest son and second child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He became king in 1901 and proved popular in his short reign.

Edward’s main interests lay in foreign affairs, and in military and naval reform. He enjoyed the sporting and social life and the Edwardian period came to embody a break with the 19th century and the dour image of the monarchy under Victoria.

The bronze equestrian statue was erected by public subscription and unveiled by Edward’s son, King George V, in July 1921. Designed by Sir Bertram Mackennal, it stands on a stone plinth by Sir Edwin Lutyens – who designed the Cenotaph in Whitehall – in a position formerly occupied by a statue of Lord Napier of Magdala.

King James II

Trafalgar Square, Westminster

James II of England and VII of Scotland (1633–1701) was the son of Charles I and the younger brother to Charles II, whom he succeeded. His reign (1685–8) was controversial, including attempts to rule by decree, concerns over religious toleration, and allegations over the paternity of his heir.

As Duke of York and king, he was governor and the largest shareholder of the Royal African Company, which managed the trading of enslaved peoples in West Africa.

The bronze statue, created in 1686 by Grinling Gibbons and Peter Van Dievoet, portrays the king as a Roman emperor. It originally stood outside Whitehall Palace, but was moved to the garden of Gwydyr House in 1897, to St James’s Park in 1902–3, and finally to its present site in 1946.

King William III

St James’s Square, Westminster

King William III (1650–1702) was born Willem Hendrik of Orange-Nassau, Prince of Orange, the son of Willem II of Orange and Princess Mary, daughter of Charles I. He married Mary, daughter of James, Duke of York, in 1677, and later came to power in the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688–9. He was leader of the coalition against Louis XIV of France in the Nine Years’ War (1688–97) and was thus a major figure on the European stage. In Ireland he remains a divisive figure, revered by Ulster Protestants and reviled by Catholics for his victory at the Battle of the Boyne (1690).

The equestrian statue by the sculptor John Bacon Junior shows William wearing Roman armour and was erected in 1808. The horse’s rear right hoof is shown grazing a molehill on which it is said to have stumbled, causing William's death.

Lord Curzon

Carlton House Terrace, St James’s

George Nathaniel Curzon (1859–1925), later Viscount Curzon of Kedleston, was Viceroy of India (1899–1905) and Foreign Secretary (1919–24).

As Viceroy, Curzon instigated a number of ‘reforms’ to Indian life, from the police and the railways to education and conservation. An ardent imperialist, his rule was also notable for a controversial partitioning of Bengal and he was accused of culpable inaction over famine.

Back in Britain, Curzon was a leading opponent of female suffrage. His interests in the arts and conservation led him to restore Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire and Bodiam Castle in Sussex.

The bronze statue by the Australian sculptor Sir Bertram Mackennal was unveiled in 1931 by Stanley Baldwin, who had pipped Curzon to the post of Prime Minister in 1922.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Read more on Curzon

Lord Herbert of Lea

Waterloo Place, St James’s

Sidney Herbert (1810–61) was MP for Wiltshire from 1832 and had a distinguished public career, serving as Secretary at War in 1845–6, 1852–4 and again in 1859. He is most remembered for his efforts, in league with Florence Nightingale, to reform standards of health care in the British Army during and after the Crimean War (1853–6). He was created Lord Herbert of Lea shortly before his premature death in 1861.

The statue by JH Foley was erected outside the old War Office in Pall Mall in 1867. In 1914 it was moved to Waterloo Place where it forms a group with the Guards Crimean War Memorial and the statue of Florence Nightingale. Around the base of the figure of Herbert, shown as a thinker rather than a man of action, are three bronze bas-reliefs showing scenes in his career and his family’s armorial bearings.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Lord Napier of Magdala

Queen’s Gate, Kensington and Chelsea

Robert Cornelis Napier, 1st Baron Napier (1810–90), was a military engineer and officer in the British Indian Army. He played important roles in the first and second Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845–6 and 1848–9), the suppression of the Indian Mutiny (1857–9) and the second Opium War (1856–60). His peerage commemorates his 1867–8 campaign in Abyssinia, now Ethiopia, rescuing European hostages from the fortress of Magdala.

British looting of the fortress and churches saw important manuscripts and objects carried away for auction; calls are still continuing for their restitution to Ethiopia from British collections.

The 1891 bronze equestrian statue by Sir Joseph Boehm originally stood in Carlton House Gardens, being moved to Queen’s Gate in 1921.

Read more on statues and the history of empire

Lord Portal of Hungerford

Victoria Embankment Gardens, Charing Cross

Charles Portal (1893–1971) was a bomber pilot during the First World War, later becoming one of Britain’s senior military leaders as Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command during the Second World War, and then as Chief of the Air Staff (1940–45).

He controversially championed strategic area bombing, which involved the intensive bombing of German cities, deliberately targeting civilian populations. While Portal and others certainly believed the strategy would shorten the war, thereby saving Allied lives, by March 1945, when it was finally halted, 350,000 German civilians are thought to have been killed by British and American bombing.

The statue by Oscar Nemon is placed prominently in front of the Ministry of Defence Building in Victoria Embankment Gardens. It was unveiled by Harold Macmillan in 1975.

Lord Trenchard

Victoria Embankment Gardens, Charing Cross

Hugh Montague Trenchard (1873–1956) joined the British Army in 1893. He served in India, in South Africa during the Boer War, and in Nigeria. He joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and served as its commander (1915–17) during the First World War.

As Chief of Air Staff between 1919 and 1930, Trenchard ensured that the Royal Air Force, created in 1918 by amalgamation of the Army’s RFC and the Navy’s Royal Naval Air Service, survived and continued as an independent command. He is widely considered ‘the father of the RAF’.

The statue to Trenchard, by William McMillan, was unveiled in 1961.

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Park Crescent, Marylebone

Prince Edward Augustus (1767–1820) was the fifth child of King George III and Queen Charlotte, and was father to Princess Victoria, later Queen Victoria. From 1791 to 1800 he resided in Canada, initially as a regimental commander, and ultimately as Commander-in-Chief of British forces.

He was Governor of Gibraltar in 1802, but was recalled in 1803 after the brutal discipline that he imposed on the garrison caused a mutiny. This ended his military career and stained his reputation. In other respects he adopted liberal attitudes, supporting Catholic Emancipation, and Bible and abolitionist societies. In 1818 he married Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld: their daughter, Princess Victoria, was born in June 1819.

The statue by Sebastian Gahagan was commissioned by charities which the duke had supported and was unveiled in 1824.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Prince George, Duke of Cambridge

Whitehall, Westminster

Prince George (1819–1904) was born in Hanover, the son of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, youngest son of George III. He succeeded to his father’s title in 1850. He began his military career in the Hanoverian army, before becoming a colonel in the British Army in 1837. He served in the Crimean War (1853–6), and was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of the Army in 1856. Over his 39 years as Commander he became notorious for his resistance to all measures of army reform. Historians have argued that he bore much responsibility for the deep-seated problems in the Army that were exposed by the Second Boer War (1899–1902).

The sculptor of the equestrian statue, unveiled in 1907, was Captain Adrian Jones, who was also responsible for the Wellington Arch Quadriga.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Queen Anne

Queen Anne’s Gate, Westminster

Queen Anne (1665–1714) was the daughter of James, Duke of York – the future King James II – and his first wife, Anne Hyde. She rejected her father’s Catholicism, supporting the revolution which removed him from the throne in 1689. Her reign was marked by the Union of England and Scotland in 1707: Anne was thus the last Queen of England and the first Queen of Great Britain. Her government controversially granted the monopoly to the South Sea Company, in which the Crown held shares, for the trade of enslaved Africans to South America.

The Portland stone statue represents Queen Anne in her coronation robes. The sculptor is unknown, but it was repaired by John Thomas in 1862, who re-carved the face using Francis Bird’s statue of the queen, outside St Paul’s cathedral, as a model.

Queen Anne (formerly identified as Queen Charlotte)

Queen Square, Holborn

It is believed this statue represents Queen Anne (1665–1714), the daughter of James, Duke of York – the future King James II – and his first wife, Anne Hyde. Her reign was marked by the Union of England and Scotland in 1707: Anne was thus the last Queen of England and the first Queen of Great Britain. Her government controversially granted the monopoly to the South Sea Company, in which the Crown held shares, for the trade of enslaved Africans to South America.

However, the statue may represent Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, rather than Queen Anne – at some point its identity became lost. Commissioned by William Strode, it may have been executed by the Cheere workshop, who specialised in lead statues.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Robert Clive

King Charles St, Westminster

Robert Clive, first Baron Clive of Plassey (1725–74), played a founding role in establishing British rule in India. His military reputation was made during the siege of Arcot (1751) and at the battle of Plassey (1757). Through the East India Company, Clive became effective ruler of Bengal, being appointed governor in 1765. These three events are depicted in relief panels on the statue.

Clive’s conduct in India made him a controversial figure in his lifetime and today. He was accused of misappropriation of funds and oppressive taxation, which exacerbated a destructive famine. The statue is inscribed ‘Clive of India’: more accurately, he oversaw an early part of its subjugation and exploitation by Britain.

The statue, by the Scottish sculptor John Tweed, was unveiled in 1912. Originally sited outside Gwydir House, in 1916 it was moved to its current location, outside the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Read more on Clive

Samuel Plimsoll

Whitehall Gardens, Westminster

Samuel Plimsoll (1824–98), was a politician and social reformer. His ‘Plimsoll line’, which marks the extent to which a ship may be safely immersed, greatly improved safety by protecting against overloading.

Known as ‘the sailor’s friend’ for his campaign against ‘coffin ships’, in later life Plimsoll also protested against ‘cattleships’ and the transport of live animals by sea.

The statue, a bronze bust on a granite pedestal supported by life-size figures of a barefoot sailor and a semi-clad Justice, was designed by FV Blundstone and unveiled in August 1929. It was erected by members of the National Union of Seamen, of which Plimsoll was an honorary president.

Simón Bolívar

Belgrave Square, Belgravia

Known as ‘El Libertador’, Simón Bolívar (1783–1830) was a military and political leader who led the independence movement in the northern parts of South America in the 1810s and 1820s.

Bolívar had spells as ruler of Greater Colombia and later of Peru. He was instrumental in securing independence from the Spanish Empire for Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Panama, Ecuador and Bolivia, which is named after him.

The statue, a gift from the six countries that he liberated, was completed in 1974 by Hugo Daini and unveiled by James Callaghan, the British Foreign Secretary.

The plinth features a quotation from Bolívar: ‘I am convinced that England alone is capable of protecting the world’s precious right as she is great, glorious and wise.’ He visited London in 1810 to seek support for his cause.

Read more on Bolívar

Sir Arthur Harris

The Strand, Westminster

Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris (1892–1984) fought as a soldier in German South-West Africa and later as an airman in Europe, during the First World War. In the 1920s he served in India, Mesopotamia and Egypt as a Royal Air Force officer.

He is remembered as the head of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command (1942–5) during the Second World War, when he implemented the Anglo-American policy of strategic bombing of German factories and cities, causing great damage to the German war effort. This came at a cost: the death of numerous aircrews and in some places, many civilians too.

The statue, by Faith Winter was erected in 1992, outside St Clement Danes church.

Read more

Sir Colin Campbell

Waterloo Place, St James’s

Sir Colin Campbell (1792–1863) was a soldier who rose from humble origins to the highest military rank. He served in the Peninsular War (1808–13) and was involved in several of Britain’s imperial wars. In the Crimean War, he commanded the Highland Regiment, his soldiers forming the ‘thin red line’ whose resistance to Russian assault won the Battle of Balaklava (1853). During the Indian Sepoy Rebellion (1857–8) Campbell was made overall commander of the British forces. He was raised to the peerage as Baron Clyde of Clydesdale in 1858, and to full Field Marshal in 1862.

The statue made by Carlo Baron Marochetti, was unveiled in 1867. It features a standing figure of the Marshal and below, on a broad pedestal, is a figure of Britannia reposing on a lion, related to Marochetti’s lions in Trafalgar Square.

Sir John Franklin

Waterloo Place, St James’s

John Franklin (1786–1847) was a naval officer and Arctic explorer who also served as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania, (1837–43). He is best remembered for his surveys of the Arctic – his third journey became the worst disaster in the history of British polar exploration.

In this last expedition (1845) Franklin and his entire crew perished while attempting to navigate the Northwest Passage in the North American Arctic. The bronze standing statue of Franklin is accompanied by the names of all 129 men who died. It was designed by Mathew Noble and unveiled in November 1866.

Photo: Tracy Jenkins/Art UK

Sir John Lawrence

Waterloo Place, St James’s

Born in Yorkshire of Ulster Protestant descent, John Laird Mair Lawrence (1811–79) was Viceroy of India (1864–9).

As governor of the Jullundur and Hill States regions, he sought to end customs such as suttee (the burning of widows) and female infanticide. He later played a major role in the suppression of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 by sepoy troops. As Viceroy, Lawrence sought to lighten the tax burden on poorer Indians and kept India out of a threatened Afghan war, but his viceroyalty was marred by the Orissa famine of 1866, in which a million people died.

The statue, by Sir Joseph Boehm, was erected in 1885 by subscription from Lawrence’s friends in Britain and India.

Sir Thomas Cubitt

St George’s Drive, Pimlico

The master builder Thomas Cubitt (1788–1855) was responsible for many renowned residential developments across London during the first half of the 19th century.

Born in Norfolk, Cubitt trained as a carpenter. His first speculative developments were in Highbury, Stoke Newington and Barnsbury, from where he moved on to Bloomsbury, Belgravia and Pimlico.

Cubitt promoted social and environmental improvements – from public parks to sanitation – and also worked on Buckingham Palace and Osborne House for Queen Victoria.

The bronze statue, by William Fawke, was unveiled in May 1995, and lies close to the site of Cubitt’s workshops.

Sir Walter Ralegh

Greenwich Peninsula, Greenwich

Walter Ralegh (also Raleigh) (1554–1618) was an English soldier, explorer, poet and sometime court favourite of Elizabeth I.

Ralegh fostered early attempts at English settlement in America in 1585 and 1587 at Roanoke, Virginia. He explored Guyana and eastern Venezuela in 1595 and 1617 while looking for a mythical city, El Dorado. As a soldier he served against the Spanish during the Great Armada (1588), at Cadiz (1596), and the 3rd Armada (1597).

Ralegh’s poetry is highly regarded and includes ‘The Lie’ and ‘The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd’.

He was executed for treason in 1617.

The statue by William McMillan was unveiled in 1959 in Whitehall but moved to Greenwich in 2001.

Read more on statues and the history of empire

Viscount Alanbrooke

Whitehall, Westminster

A soldier in the British Army from 1902, Alan Francis Brooke (1883–1963) served during the First World War and reached the rank of lieutenant colonel. He became known for his ability in planning complex operations.

During the Second World War, Brooke commanded the II Corps of the British Expeditionary Force, including during its retreat to Dunkirk. In July 1940, as Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, he planned Britain’s anti-invasion defences.

From December 1941–5, Brooke was Chief of the Imperial Defence Staff, the principal military adviser to the British government and its allies, and in command of the British Army, playing a major part in the strategic direction of the war effort.

The statue, by Ivor Roberts-Jones, was unveiled in 1993.

Viscount Slim

Whitehall, Westminster

William Joseph Slim (1891–1970) was a career soldier of outstanding ability who fought in both world wars of the 20th century.

He is remembered for his brilliant command of the 14th ‘Forgotten’ Army in Burma (1942–5). Allied forces there had been systematically defeated by the Japanese. Slim re-trained his army for jungle warfare, with new tactics and efficient supplies, and succeeded in halting the Japanese advance through Burma towards India, which contributed, in 1945, to Allied victory.

Slim was greatly respected by soldiers fighting for the Allied cause in Burma, who represented many nationalities – British, Indian, African, Chinese, American and Burmese.

The statue, by Ivor Roberts-Jones, was unveiled in 1990.

Explore more

-

London Statues and the History of Empire

We look at Britain's colonial history through the individuals commemorated in our statues, recognising that many have committed historical wrongs that need to be acknowledged today.

-

Monuments Gallery

We care for nine public monuments in London, including Marble Arch, Wellington Arch and the Cenotaph. Explore the full gallery here.

-

More Histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.