Richard

Richard was the eldest of eight children born to the 3rd Baron Braybrooke and his wife, Jane. He spent his early childhood with his four brothers and three sisters at Audley End House in Essex, a household that was enriched by his parents’ wide range of interests in all aspects of history.

Richard was a pupil at Eton College from 1832, frequently writing to his mother and sending her poems. At home he was given a cabinet to display the items he collected, which included all kinds of natural curiosities and ancient artefacts.

Leaving school in 1837, he joined the 1st Grenadier Regiment of Foot Guards, appointed an ensign and lieutenant. His battalion was deployed to Canada in 1838 to quell a rebellion by French Canadians. Though there was relatively little fighting, Richard recounts in his diary an unfortunate accident where he fell into the St Lawrence river and nearly drowned.

His diary stops abruptly in May 1840 and he returned to England in October of the same year. Resigning his commission in September 1842, Richard ended his army career when he was only 22. He married Charlotte Graham Toller, sixth daughter of the 2nd Earl of Norbury, in 1852 and they had four children. On his father’s death in 1858 he assumed the title of 4th Baron Braybrooke.

Collector and Antiquarian

From childhood, Richard collected and exhibited items that fascinated him. Fossils and geological samples were an early interest. Taxidermy followed closely, and by 1840 we are told there were 99 cases in the Audley End collection. Some birds came from the aviary and estate, others from further afield; one shipment of 136 specimens came from Fremantle, in Western Australia. The collection was later recognised as one of the best in the locality.

From 1844, Richard spent more time in the pursuit of the past. Over a period of 11 years he visited Roman and Anglo-Saxon sites across Essex and Cambridgeshire – directing excavations, collecting and writing about what he discovered. One important site was the Roman station at Chesterford, a village close to Audley End, which he described as his ‘El Dorado’.

Elected to the Society of Antiquaries in 1847, he began to publish articles in the various archaeological journals of the time. He created the ‘Museum Room’ – a large room on the ground floor of Audley End, which housed an impressive collection including Roman Samian ware, finger rings spanning 2,000 years, and an array of ancient coins. From signatures left in the Museum Room visitors’ book we see that over 200 members of the Royal Archaeological Institute visited, many of them leaders in their respective fields.

Image: The front cover of Richard’s visitor book for his Museum Room at Audley End, dated 1848

© Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Health and Disability

From various sources close to Richard, including writings from the man himself, we know that he suffered from a health condition that was both chronic and significantly debilitating throughout his adult life. The Cambridge academic and diarist Joseph Romilly, a frequent visitor to Audley End, recorded that Richard did not dine with the family. In diary entries between 1844 and 1847 he refers to Richard as ‘the most miserable looking object’, ‘a mere hopeless wreck’, who is ‘hardly ever seen’.

At the same time that Romilly is writing these comments in private, Richard himself writes in the dedication of his publication Antiqua Explorata (1847) that he hopes his grandmother will ‘make more than due allowance for his illness’. He says that the state of his health precludes ‘the possibility of taking part in violent exercise’.

In his second monograph, Sepulchre Exposita (1848), he comments on his mother’s care during ‘long and painful illness’, and that he had been suffering from exhaustion, fatigue, a lack of strength and poor general health. His younger sister Lucy also mentions her concern for Richard’s health in her own diaries. However, despite these frequent references to his poor health, it is not clear from Romilly, Lucy or Richard what it is he may have been suffering from.

Two medical men

Other clues as to Richard’s condition come from the presence of two companions who appear frequently at his side throughout his life, both of whom are medical professionals.

JD Wright, a surgeon-major, is first mentioned by Richard when he treated him in Canada for an injury to his heel. Wright’s visits to Audley End are recorded by Richard’s sister Lucy, and he also appears when there is mention of Richard being unwell. On 21 November 1841 Lucy writes ‘Dick having left off the medicine for 7 weeks now again taken ill. Mr Wright came.’

John Lane Oldham was indentured as an apothecary in Manchester and from his account books we know that he was paid a quarterly salary by Richard’s father. It is also clear that he was on friendly terms with all Richard’s siblings – socialising with them, lending and borrowing money and playing games with them. He joined the family for dinner and travelled with them. More than an employee, Oldham was a companion of a similar age to Richard, with medical training. He later took holy orders and became the family chaplain.

Both Wright and Oldham were involved in Richard’s archaeological pursuits. What was it that required Richard to have this trained medical support on hand for most of his adult life?

Sudden Death

‘Just after 12 o’clock at night it pleased God to take from us almost instantaneously my dearest Brother’

Lucy’s entry in her diary, 22 February 1861

Richard was only 41 years of age when he died suddenly. It is clear from Lucy’s diary entry that her brother’s death took the family by surprise. She writes that the family had been ‘more sanguine about his health and less prepared for this awful shock’.

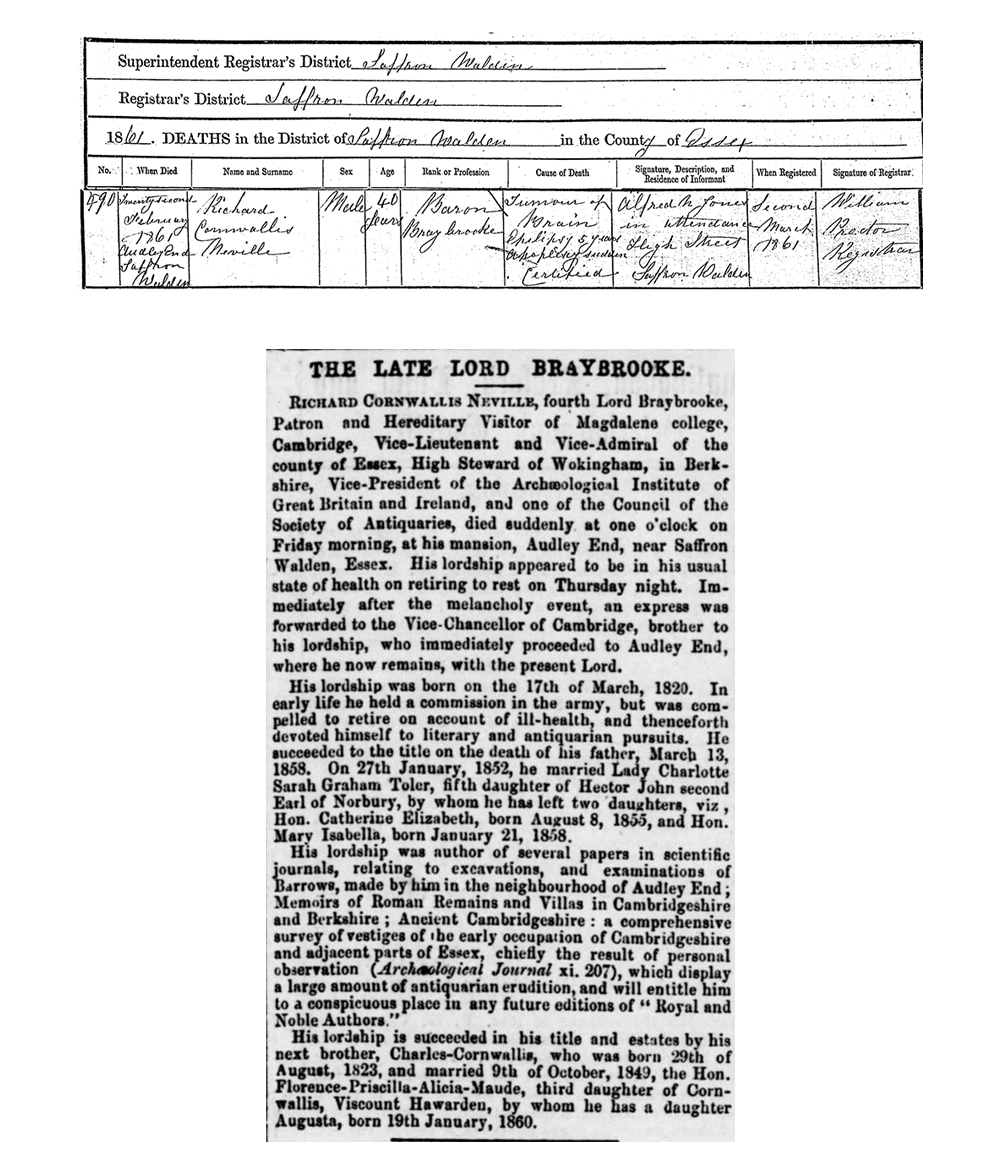

Richard’s death certificate gives us, for the first time, some information about his medical condition. He is described as having died due to a ‘tumour of the brain, epilepsy, sudden apoplexy’.

Richard’s health had always been a concern for the family, as recorded in Lucy’s diaries, but the term ‘epilepsy’ is never mentioned by her. From the autumn of 1856, Lucy had occasionally mentioned that Richard had been unwell, but she began to use the word ‘attack’ rather than ‘ill’. On 6 October she writes: ‘Dick still poorly from an attack’. She doesn’t, however, describe the nature of these ‘attacks’.

Lucy also mentions that Richard had been to see a Dr Todd in London. Dr Robert Bentley Todd was a physician who in 1849 put forward the suggestion that seizures might be caused by ‘electrical discharges’. He lectured on the pathology and treatment of convulsive diseases. Perhaps Todd was treating Richard for epileptic seizures?

Epilepsy

Knowledge of epilepsy goes back 4,000 years, the term coming from the Greek word ‘epilambaneim’ meaning ‘to seize’. Historically, it was seen as a spiritual condition, with exorcism being the main treatment for many years. The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates was one of the first to give a non-spiritual basis for epilepsy, but his ideas had little influence for many years.

By 1346 Bethlem Royal Hospital in London (also known as Bedlam) may have been the place where an individual with epilepsy could have found themselves. Treatments such as ice-cold baths, beatings, bleeding by cupping or the ‘strait waistcoat’ were employed. After the closure of Bedlam those suffering from the ‘falling sickness’, as epilepsy was known at the time, may have been sent to an asylum, shunned and shut away from society, a family secret.

Epilepsy in the 18th and early 19th centuries was a condition shrouded in mystery. It carried a social stigma and made it difficult for those suffering to find a marriage partner or employment. There was much discrimination against and challenge for those with epilepsy. Some physicians such as Dr Robert Bentley Todd began to accept that it was a brain disorder. Todd is also known to have prescribed potassium bromide which became known as an effective treatment.

Image: A watercolour probably from the late 17th century depicting a man suffering from epilepsy being held up in front of an altar in the hope of a miracle cure

© Wellcome Collection

Living with Disability

Some clues from Lucy’s diary give us an idea of how Richard’s condition affected his life. When he married in 1852, Lucy expresses her delight and previous fear that such an event would never take place – he had remained unmarried longer than one might expect for an heir. This was shortly followed by serious concern when Richard’s return from London to Audley End after the marriage was delayed, due to him being too unwell to travel.

Richard’s health was also likely the reason for his early retirement from the army, and much of his life between 1841 and 1847 is characterised by his non-appearance at social occasions such as family dinners. His personal appearance gives rise to comment, he is described as unkept, dishevelled, fatigued, exhausted and lacking strength, and it seems his weakness is common knowledge in the locality.

There is, however, a bright spot in this unhappy situation. Richard’s interest in archaeology brings great improvement in strength and general health – he writes that he ‘derived so much benefit from my Cambridgeshire excavations’ that he looked for fresh areas to research. It was not only the finding and excavating, but also the recording and reporting of the work that gave him renewed ‘powers of mind and body’.

This change was remarked on by Romilly, who noted how Richard took great satisfaction in sharing his discoveries. No longer shying away from society, he guided visitors around his Museum Room, discussing his collections of rings and coins with guests. Romilly describes being taken to the site at Chesterford where 20 rooms of a villa had been uncovered. Richard was also publishing papers regularly and giving talks to local societies.

Richard’s Legacy

Baron Braybrooke for just under three years, Richard deserves to be recognised as an individual who has left an important legacy, and not only in the rooms and on the walls at Audley End. His contribution to the knowledge and understanding of ancient Cambridgeshire and Essex with regard to Roman, Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon life is particularly notable. Visitors to Saffron Walden Museum can view exhibits displaying objects he was responsible for excavating.

Though the Museum Room at Audley End no longer exists, many of the contents form part of the collection of more than 700 items which now rest within the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The many articles Richard wrote about the excavations undertaken help us to understand the workings of the Victorian antiquarian and are often referenced in modern work. Rings and coins from his collections are part of the collections held at the British Museum.

In his writings, Richard tells us that his interest in archaeology has provided him with a reason to exert himself, and that he gains real benefit from the mental and physical aspects of his research. Without his ‘illness’ perhaps none of this would exist. If he had remained in the army would he have suffered the same fate as his brothers Henry and Grey, who lie in graves in the Crimea?

He was fortunate in many ways – loved by his family, a man of means, titled, educated, and with military experience. All this allowed him to follow his passion despite his health condition. He was highly regarded by his peers, having one of the most prestigious private collections of his day, and was generous in the sharing of his results. Although he suffered for many years from an unpredictable illness, it could be said that this gave him other opportunities, and a chance to follow a different path.

By Denise Hall

Header image: A watercolour of the Museum Room at Audley End from around 1850

© Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Explore more

-

History of Audley End

Read a full account of Audley End’s long and varied history, from the priory founded on the site in the 12th century to the present day.

-

Living with Disability

London’s blue plaques scheme commemorates people from all walks of life, some of whom – as would be expected – lived with a disability. We explore stories of people with both visible and hidden impairments, and consider the impact disability had on their lives.

-

SILENT UNSEEN: THE POLISH SPECIAL AGENTS OF AUDLEY END

During the Second World War, Audley End was used as a training base by the Polish Section of the Special Operations Executive. Discover their incredible story.