Capability Brown and the war of words at Audley End

How a contract in 1763 between England’s foremost landscape gardener and a landowner with a military past deteriorated into a furious exchange of letters.

THE LANDSCAPE GARDENER

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown was England’s pre-eminent designer of landscapes. Immensely prolific, he transformed upwards of 250 gardens and parklands in England and Wales from the 1740s until his death in 1783, and is remembered for ushering in a sweeping, informal landscape style. His account book for 1764 shows a gross income of about £6,000 – just 20 years earlier, Brown had been earning £25 a year as head gardener at Stowe.

THE SOLDIER

Sir John Griffin Griffin of Audley End is listed in Brown’s 1764 account book. He had been a career soldier called John Griffin Whitwell before he inherited Audley End at the age of 53, from his mother’s sister. Under the terms of his inheritance, he had to change his paternal name to Griffin – hence the new double name.

At Audley End, Sir John commissioned Robert Adam to remodel the reception rooms and redesign a bridge in the park. He also agreed a contract of work with ‘Capability’ Brown which included widening the River Cam to create the appearance of a linear lake, as well as new driveways and lawns, and extensive tree planting – all to be achieved within 13 months (by May 1764), for the sum of £660. Sir John was to provide the trees, shrubs, tools and wheelbarrows.

DELAY

It was a substantial scheme, and Sir John wrote that the work ‘was very backward at the latter end of 1764 – when I was neither satisfied with the delay, nor with the manner in which some of its parts were finishing’. But the agreed £660 was paid and the work continued, either with a second contract or by ad hoc arrangement, until May 1767, when Sir John paid Brown a further £150 ‘for his trouble’.

However, Brown wrote a letter to Sir John five months later, in October 1767. He said that as he’d had to sell some stocks to fund the work, Sir John should pay his lost interest, amounting to just over £94. Sir John was adamant that he owed nothing. Perhaps unwisely, Brown finished his next letter with the words:

I assure you I cannot humble my mind to act on so narrow a principal, I dare say if I could I should have been richer and perhaps wiser. Do not think Sir that I trouble you with this for redress, I do it to justify my own conduct in the demand I made on you.

‘MR BROWN INFORMS SIR JOHN …’

A frosty silence ensued, and when the correspondence was renewed in February 1768, Sir John addressed Brown in the third person:

though it requires no answer yet as a total silence might perhaps induce Him to think that Sir John was better satisfied than he was before the receipt of his letter, in regard to the interest money He refers to.

Brown’s response ten days later is equally cool, beginning:

Mr Brown informes Sir John Griffen that he has received his note and as Sir John meant to say nothing that was agreeable to Mr Brown after seven months silence it would have been as well to let It sleep on …

The incorrect form of Sir John’s name is probably down to the fact that in an effort to keep up with his increasing workload, Brown had hired an accounts assistant who was unfamiliar with client names. What is clear is that Brown goes on to accuse Sir John of being unforgiving, dishonourable and blinkered. He concludes:

Mr Brown had neither thought of Sir John nor the money from that time to this, and had forgot & forgave, being perfectly sure that Sir John & him will never have any disagreement more in business nor money matters but at the same time assures Sir John that he continues in the same mind in regard to the interest & thinks him self not honourably treated in that respect. Mr Brown will never labour more to convince Sir John as he knows there is non so blind as him that will not see.

THE WRONG BEND

The final item of correspondence is from Sir John, and it sets out his dissatisfaction over the work’s delay and cost. He is adamant that ‘what money he called for, I never refused payment’ and that Brown ‘never advanced one shilling for I paid the Labourers & his foreman as work went on’. He also accuses Brown of creating ‘a wrong bend to the River, & contrary to his own Plan’. A plan attributed to Brown (below) does indeed show the river bending the opposite way to its final execution.

The garden’s final design does not reflect the turmoil involved in its creation. The sweeping lawns and river serenely stretch out before the front of the house, encapsulating Brown’s overall vision.

By Emily Parker

- Find out more about Capability Brown

- Read more about Audley End’s history

- Visit Audley End House and Gardens

Georgian Stories

-

Capability Brown at Audley End

How a contract in 1763 between England’s foremost landscape gardener and a landowner with a military past deteriorated into a furious exchange of letters.

-

Black Prisoners at Portchester Castle

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in 1793, the islands of the Caribbean were drawn into the conflict. In 1796 free black soldiers were captured and sent to Portchester as prisoners of war.

-

Romantic Female Friendship

In the 18th century, among fashionable women, a cult of same-sex ‘romantic friendship’ was accepted, even if to some contemporary observers it appeared ‘queer’

-

The Invention of the Wellington Boot

How the Duke of Wellington, victor at the Battle of Waterloo and fashion icon, gave his name to the humble welly.

-

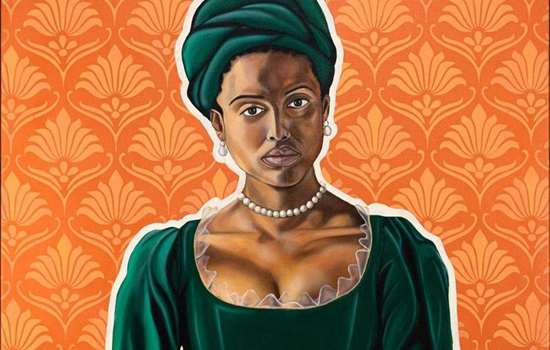

Dido Belle

A mixed-race woman, Dido Belle was raised as part of an aristocratic family in Georgian Britain at the height of the transatlantic slave trade.

-

Philip Thicknesse, Landguard's Loosest Cannon

How Philip Thicknesse finally got his comeuppance after a madcap life of self-inflicted scandal in 18th-century England.

-

The Only People Ever Killed at Tilbury Fort

The only fatalities ever reported at Tilbury Fort were thanks to a game of cricket in 1776. Or is this extraordinary story just a tall tale?

-

An Emperor and an Aristocrat's Menagerie

How the 19th-century menagerie at Chiswick House in west London was part of a wider tradition of keeping exotic creatures on aristocratic estates.

More about Georgian England

-

Georgians: Parks and Gardens

The growing fashion for scenery in the Georgian period, accompanied by theories on nature, led to more naturalistic landscape designs that were an early expression of Romanticism.

-

Georgians: Power and Politics

Until the very end of the Georgian period, power belonged almost exclusively to those who owned substantial land or wealth.

-

Georgians: Architecture

The classic Georgian building is the Classical country house. But this is also the period that saw the first steps towards a coherent approach to town planning.

-

Georgians: War

For much of the Georgian period Britain was at war – usually with France. Many of these conflicts were played out on a world stage, to defend or expand the burgeoning British Empire.