NORTON, Caroline (1808–1877)

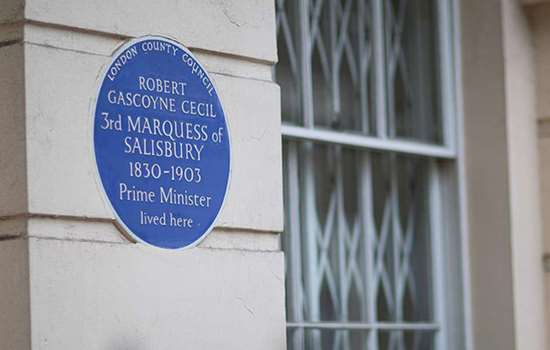

Plaque erected in 2021 by English Heritage at 3 Chesterfield Street, Mayfair, London, W1J 5JF, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Champion of women’s legal rights

Category

Law and Law Enforcement, Literature, Philanthropy and Reform

Inscription

CAROLINE NORTON 1808–1877 Champion of women's legal rights lived here 1845–1877

Material

Ceramic

Caroline Norton campaigned extensively for the legal rights of women who were separated from their husbands. She was instrumental in the passage of the 1839 Custody of Infants Act, which has been described as the first piece of feminist legislation. Norton was also highly regarded as a writer during her own lifetime. Her blue plaque at 3 Chesterfield Street in Mayfair marks the house she lived in for over 30 years.

MARRIAGE TO GEORGE NORTON

Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Sheridan was born in London, the granddaughter of the playwright and politician Richard Brinsley Sheridan. She married George Chapple Norton in 1827, aged 19. It was a catastrophic mismatch from the start: she was quick-witted, vivacious, and an ardent Whig, he was dull-witted, indolent and a High Tory. Caroline also soon found that George drank excessively and resorted to physical violence in their disputes, a frequent cause of which was lack of money. Their financial pressures increased with the birth of three sons – Fletcher (1829–59), Brinsley (1831–77) and William (1833–42) – and Caroline was forced to support the family with her writing.

It’s more than likely that she had an affair with the Home Secretary and later Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, at around this time. Caroline’s relationship with George, meanwhile, continued to deteriorate, and she left the marital home in 1835 but quickly returned when George denied her access to the boys. In March 1836, after yet another quarrel, George locked her out of the house, took the children to his family home in Surrey, and refused to let Caroline see them.

FIGHT FOR CUSTODY

George attempted to sue Melbourne for adultery with his wife, but Melbourne was acquitted when it was found that many of the witnesses had been paid to commit perjury. The acquittal meant George couldn’t divorce Caroline. However, he still prevented Caroline from seeing their three sons, taking full advantage of the existing law which automatically gave custody of children to their father.

Caroline began a fight to change that law. She published two pamphlets, in 1837 and 1838, and asked the lawyer and MP Thomas Talfourd to sponsor a child custody bill through Parliament. After this initially failed she kept up her lobbying, producing A plain letter to the Lord Chancellor on the Infant Custody Bill (1839). In that year the Custody of Infants Act was finally passed, by which legally separated or divorced mothers who had not been found guilty of adultery were given custody of children under seven, and granted regular access thereafter.

Caroline finally gained shared custody of her children in 1841, though William tragically died of tetanus the following year.

FIGHT FOR PROPERTY RIGHTS

In March 1852 George cancelled Caroline’s allowance and refused to honour his liability for her bills. He also resumed his practice of channelling her earnings into his bank account, which he was legally entitled to do, since (unless there was a pre-nuptial agreement) a wife’s earnings and property belonged to her husband.

With no legal identity of her own, Caroline was unable to sue or be sued, raise her own contracts, receive legacies or make a will. However, in 1853 she asked her creditors to sue George on her behalf. Caroline defended herself vigorously in court, and was received with cheers, but the court found in favour of George on a technicality. ‘I do not ask for my rights,’ Caroline said in response. ‘I have no rights; I have only wrongs.’

For some weeks the financial and emotional matters of their marriage dominated the letter columns of The Times, and Caroline began to campaign for changes in the law relating to married women’s property rights. Her first move was a privately-printed pamphlet, English laws for women in the nineteenth century (1854), in which she used her own grievances to persuade Parliament to protect the property and income of married women. Her A letter to the Queen on Lord Chancellor Cranworth’s Marriage and Divorce Bill (1855) argued the case for property rights for divorced and separated women, and helped shape what eventually made the statute book as the Matrimonial Causes Act (1857). Four clauses were directly derived from her pamphlet, including that a separated wife was to be regarded as unmarried, meaning she could control her own finances and property.

Caroline Norton, however, was no feminist in the modern sense of the word. In A letter to the Queen she wrote:

The natural position of woman is inferiority to man. Amen! That is a thing of God’s appointing, not of man’s devising. I believe it sincerely, as a part of my religion: and I accept it as a matter proved to my reason. I never pretended to the wild and ridiculous doctrine of equality.

She had no interest in attacking the institution of marriage, and did not wish to make divorce easier. Her aim was to establish the existence of separated women in law.

CHESTERFIELD STREET AND WRITING CAREER

Caroline secured the lease to 3 Chesterfield Street in 1844, and wrote wistfully about the move from her noisy temporary lodgings:

I have not been able to get any more of my book done, but I think when I can get there, where it is all very quiet overlooking Ld Wharncliffe’s garden instead of this paved street, my head will be better & I shall get the book done – after which I will be very idle for a while & will paint a little by way of complete change.

Although her mother and son Fletcher joined her for short periods, Caroline mainly lived alone and unchaperoned in the house, where she entertained guests, and supported herself with her writing – an unusual arrangement for the time that kept tongues wagging.

During her lifetime Norton was well regarded as a poet and novelist. Coleridge’s nephew and editor called her ‘the Byron of our modern poetesses’. She wrote prolifically, and her output included novels, long narrative poems, children’s fiction, short stories, songs and a play. Her natural talent, however, was perhaps overwhelmed by the need to make a living, as she was forced to source most of her income from contributions to magazines and periodicals, and from editing several annuals. Today Caroline’s poems are occasionally anthologised, but her reputation as a writer has declined since her death.

Because Caroline had left George but gone back to him in 1835, she was never able to divorce him. However, in 1859, a deed of separation was finally agreed between them, leaving her free to live as if she was unmarried. She continued to write, but her health was deteriorating and she spent a lot of time caring for her sons and grandchildren: Fletcher died of tuberculosis in 1859, while Brinsley, who possibly suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, caused her much distress.

Having been fully freed by George Norton’s death in 1875, Caroline married an old friend, the widowed Sir William Stirling-Maxwell, on 1 March 1877 in the drawing room at 3 Chesterfield Street. However, she died a little over three months later from peritonitis. She was buried in the Stirling-Maxwell vault at Lecropt church, near Keir, Scotland.