Roman Conquest and Early Settlement

The Roman conquest of Britain started in AD 43; however, it was not until around AD 70 that advances into the northern regions of the country began.

The establishment of a settlement at Aldborough during this time was largely due to its key strategic position. The earliest road here heads west from York into the Pennines to exploit the mineral resources. The location of Isurium at the highest navigable point on the river Ure suggests it developed as a point of trade.

In around AD 120 a carefully planned town was begun here, with a regular street grid, terracing on the hillside upon which houses were built, and a large forum and basilica at its centre. A new bridge across the river Ure created a route through the town to the north and Hadrian’s Wall. The town became a wealthy, bustling hub, with a busy to-and-fro of people and goods.

Cartimandua and the Brigantes

The name Isurium Brigantum reflects the town's status as the civilian capital of the Brigantes tribe, the largest confederation of tribes in Britain at that time. Brigantes, meaning ‘the hill people’, was a term given by the Romans to the people who occupied most of northern England.

Queen Cartimandua was ruler of the Brigantes from around AD 43. Having formed strong alliances with the Romans, Cartimandua and her husband Venutius were able to avoid invasion during the early years of the conquest. When in AD 51 Caratacus, leader of the Catuvellauni, asked her for sanctuary after his defeat by Rome, she handed him over to the Romans instead.

In AD 57 Cartimandua split from her husband, driving Venutius to wage a war against her. Although Cartimandua had the support of the Romans, Venutius took advantage of Roman instability in AD 69 and eventually took over as ruler of the Brigantes. With the Brigantes now under the leadership of Venutius and his anti-Roman supporters, the Roman invasion of the north began.

Read more on CartimanduaThriving Under Roman Rule

Excavations at Aldborough have revealed a great deal about the development of Isurium into a flourishing urban centre. The town was fortified with a stone wall in the late 2nd century, indicating its important status, and the settlement eventually sprawled well beyond its walls, perhaps an indicator of economic success.

The defences were enhanced in the 4th century by the addition of towers projecting forward from the walls, and by additional external ditches, providing an impressive appearance to the town. This suggests a more unstable society and a need to protect people and trade.

Mosaics discovered in town houses are evidence of the splendour of these buildings and indicate the existence of a wealthy elite. Various objects discovered at Aldborough – including ceramics, fragments of glass and pottery, brooches, jewellery and material associated with the Roman army – paint the picture of a prosperous and well established society with military associations and good access for trade.

Explore the Aldborough CollectionThe Helicon Mosaic

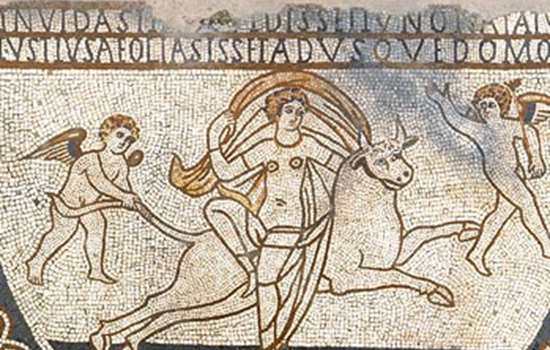

Aldborough has one of the largest numbers of mosaics of any town in Roman Britain with 22 recorded, largely from the south-western quarter of the site. Most of these would have adorned large town houses and are dominated by abstract geometric designs, made with small cubes of material (tesserae).

One of the finest among them is the Helicon mosaic, which comes from an apsidal room excavated in the 19th century. This very fine pavement dates to the early 4th century AD and includes an unusual Greek inscription in blue glass tesserae. It would have formed the floor of an apse at one end of a dining room, in a position allowing the principal guests to view and admire it from their seats or couches, while eating and talking.

The depiction of the muses in the Helicon mosaic suggests that the people of Isurium were well versed in Greek mythology and had tastes influenced by the wider empire.

Aldborough after the Romans

The fate of Isurium after the collapse of Roman power in the 5th century is a mystery. It is likely that the walled area remained in some use. Archaeological and documentary evidence suggests it remained an important settlement through the Anglo-Saxon period and by the time of the Domesday survey (1086) it was recorded as a major centre with large landholdings. A church was built in the courtyard of the Roman forum, probably before the Norman Conquest, suggesting that parts of the Roman town still stood.

In the medieval period Aldborough was a ‘borough by prescription’ and from 1558 it returned two Members of Parliament. Aldborough would become a valued possession of successive Dukes of Newcastle, who ensured that it remained a ‘pocket borough’ until the Great Reform Act of 1832. The interest in restricting the size of the village was almost certainly for the Dukes' own political influence. However, it also meant the area escaped any large-scale development and ensured the survival of the Roman town.

Excavation and Discovery

Aldborough’s Roman past has been explored through different periods of excavation and discovery. The 18th century saw two major finds: first, the discovery of a series of mosaics in the centre of the village; and second, uncovering the extensive remains of walls in 1770, which formed part of the town’s Roman forum.

However, it was not until the 19th century that the historic value of Aldborough was more fully recognised. Andrew Lawson, who purchased Aldborough manor in 1834 from the 4th Duke of Newcastle, encouraged further exploration of the Roman town.

Lawson excavated a series of buildings in the manor grounds which led to a considerable collection of Roman artefacts. He also erected buildings to protect some of the mosaics and set up a museum for displaying the archaeological finds, which opened in 1863. The museum, along with the area which makes up the English Heritage site today, was given to the State in the 1950s by his great-granddaughter Lady Lawson-Tancred.

After Lawson’s excavations in the 1830s and 40s there was comparatively little digging on the site until after the First World War. Since then, there have been various periods of excavation and surveying on the site, each contributing to a greater understanding of the town today.

Women at Aldborough

In the 20th century, many of the excavations and discoveries at Aldborough were led by women, which was still a rare occurance up until relatively recently.

Lady Margery Lawson-Tancred was a keen supporter; she wrote an excellent guidebook for Aldborough and was also responsible for inviting and encouraging women to work at the site. The first was Mary Chitty, whose work on the defences with JNL Myres and K Steer continued her research on Roman Yorkshire. Later archaeologists included Dorothy Charlesworth who, as Inspector of Ancient Monuments, was the only woman to achieve such a senior position in the Ministry of Works (now English Heritage) for some time to come.

In turn, Charlesworth commissioned Margaret Jones to carry out rescue work at Aldborough in 1964, the summer before she began excavations at Mucking, which would become the largest rescue dig of its time. The work of these women, alongside others who have worked on various archaeological sites across England, has helped shape our understanding of the past, encouraging a new generation to explore with a similar spirit of curiosity and care.

Read more about female archaeologists at our sitesAldborough Today

Aldborough is now the focus of a thriving research and community programme. In 2009 the Aldborough Roman Town Project (University of Cambridge) was established to better understand the development of Isurium and its role in the Roman north. A synthesis of all previous work has been created, drawing together evidence from antiquarians and archives.

The project has used newly available technologies to map the landscape above and below ground. Using a combination of geophysical survey techniques, detailed plots have been made of features below the ground, revealing streets lined with town houses, temples and public buildings. The walls of the forum have been discovered beneath the churchyard. Beyond the walls, the amphitheatre is visible with its curved seating.

The project team began excavations in 2016, mainly reinvestigating previous excavations. Their work has included the digging of a narrow trench to discover the precise orientation of the forum; excavating part of a large warehouse first discovered in 1924; and unearthing an area of Roman workshops, including a blacksmith's workshop.

Work continues to make sense of the origins and endings of the town, and understand more about those who lived here.

Photogrammetry has been used to record excavations, objects and structures at Aldborough, and also to assess rates of change for conservation. Explore some of the 3D models below, created by Professor Dominic Powlesland.

-

Buy the guidebook

Buy the Aldborough Guidebook to discover more about the site and its history.

-

Explore Roman Britain

In this introduction to Roman Britain, learn more about Roman daily life, politics, religion, art and commerce.

-

Hadrians Wall: History and Stories

Discover the histories, stories and mysteries associated with English Heritage’s Hadrian’s Wall sites.

-

More Histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.