Early Life

Bridget was born in 1732 to Michael Maughan (1709–37), a mining engineer, and Dorothy (née Lowthian) at Leadhills in Lanarkshire. Following her husband’s death, Dorothy returned to her Cumbrian roots to raise daughters Bridget and Jenny at Kirkoswald. The girls grew up surrounded by cousins, and were sent to Mrs Paxton’s academy in Durham where they learnt sewing and linen-dressing. Bridget’s handwriting is almost identical to her mother’s, so she was probably taught to read and write at home. Bridget’s surviving letters show that her spelling was erratic, and she rarely used punctuation.

Love and marriage

In the summer of 1756, aged 24, Bridget met George Atkinson, and he was immediately taken with her. Unfortunately, the timing was not good. Bridget’s mother Dorothy had recently broken up an engagement that her sister Jenny had made, leaving the latter heartbroken. Bridget had feelings for George but feared her mother would disapprove of the match. The Atkinson family, although respectable, were not quite of the same class, and Dorothy was pressing Bridget to marry a local gentleman instead.

Bridget’s friend Biddy wrote to encourage her to be strong:

If you can only try for a little bitt of More Spirit and Resolve to fight throw it and not Sink under The weight of what Some people would only Look on as trifels and who knows but you may yet make that worthy fellow happy that would be willing to be seven times hanged and let down agane for you, and if not him Some body else that disarves you. Never however throw your Self away on a munkey that all the World agrees is not worthy of you.

After a winter of silence when Bridget did not return his letters, in the spring of 1757 George decided to try to enlist Jenny’s help. He sent Jenny a packet of tea and a letter pleading his love for her sister. His letter worked. On 7 January 1758, George left Temple Sowerby for St Michael’s Church, Addingham. There he met Bridget who had crept away from her family for a few hours, and they were married in secret.

But before Bridget was able to break the news to her mother, Dorothy somehow found out. Bridget wrote to her sister in distress:

Dear Jenny you will use your interest to paceffy my Mother and to prevail with her to alow me to come home a Little while indeed my happiness depends upon it. I beg you’ll write soon and tell me the worst.

Bridget’s aunt, with whom she had been staying when she snuck to the church, wrote to Dorothy asking her to forgive Bridget and extolling the virtues of George.

All must have been forgiven because shortly afterwards a wedding announcement was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine: ‘Mr. Atkinson, tanner, near Appleby – to Miss Maughan of Wolsingham, Durham £3000.’

The Atkinson family were tanners – they turned raw animal hides into leather – from Temple Sowerby in Cumbria. The house George and Bridget moved into had been in the family since the 1720s. Bridget’s dowry enabled them to expand the house, which was fortunate because she and George had ten children, eight of whom survived to adulthood – Dorothy, Michael, George, Richard, Matthew, John, Bridget and Jane.

Bridget's shell collection

Bridget had a lifelong passion for shells. In her day, many women collected shells to decorate grottos or furniture. But Bridget’s collection was driven by curiosity about the world. We can see this from the geographical range of her shells, comments in her letters, and her conchology (study of marine shells) reference books. Her neighbour, Mary Yates, described natural history as enlarging the mind, and Bridget’s collection is this sort of endeavour.

Bridget’s collection covered many different species, some of which are now endangered and protected.

Bridget’s passion for shells was fondly recognised by her family. Her son-in-law Nathaniel Clayton joked that her grandchildren could come to visit provided she agreed to their return ‘under the penalty of forfeiting your whole cabinet of shells’. One of her grandsons teasingly compared her extensive collection to the collection in Parkinson’s Museum in London.

An intercontinental network

Bridget never left Britain, and rarely left the county of Cumbria, but her family and friends travelled across continents and sent her shells by ship, carriage and cart. Her son Michael was based in Bengal as an employee of the East India Company, an organisation which colonised large areas of South and South-east Asia. Bridget’s brother-in-law Richard ‘Rum’ Atkinson was a director of the East India Company, and the owner of two slave-run sugar plantations in Jamaica. Following his death in 1785, Bridget’s children inherited these estates. The Atkinson family was one of thousands of British families to benefit from imperialism.

Bridget’s shells and her letters about them reflect this colonial history as well as her enthusiasm for her collection.

On 29 July 1756, James Tinkler, a London merchant, wrote to his cousin Bridget Atkinson.

On 3 March 1796, Mary Yates of Skirwith Abbey wrote to her son John in Virginia.

On 4 November 1804, Bridget Atkinson wrote to her son Matthew in Jamaica.

On 30 December 1804, Bridget Atkinson wrote to her son Matthew in Jamaica.

A family inheritance

In her 70s, Bridget began to feel old age ‘coming on very fast’ but her letters show that she retained her passion for collecting. She concluded a letter in 1804 to her son Matthew in Jamaica by saying ‘I only will add I am as fond of Shells as ever Land or fresh water or Sea Shells’ and requesting that he send more.

In addition to collecting shells, Bridget gathered recipes. In 1806, she wrote a ‘Receipt’ book for her eldest child, Dorothy Clayton, who lived at Chesters in Northumberland. It contained almost 800 recipes, the first 500 or so of which are for food, showing the variety of dishes served at Temple Sowerby, and the range of spices and flavourings Bridget had access to. In the last third of the book Bridget wrote down remedies for a wide array of ailments and domestic problems, including To prevent Milk from having a taste of Turneps; A Pomatum for the Face after Small Pox; For worms in Children; For Berry Bushes infested with Caterpillars; To cure the Bite of a Mad Dog; To destroy Moths. Not all of these remedies would be considered safe today: ‘Mrs Atkinson’s Receipt’ consisted of rhubarb, laudanum and gin, mixed into a pint of milk. It is not known what this was meant to cure, but it would have been risky!

In 1813, at the inaugural meeting of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Bridget was elected its first honorary member. She donated to the society an ancient stone hammer, coins dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, and a Swedish coin dated 1716.

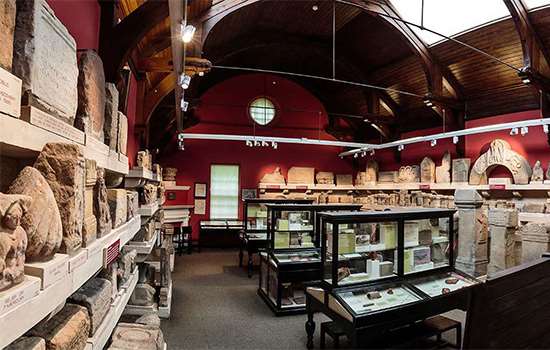

When Bridget died, she passed her collection of shells and coins to her youngest daughter. Jane (1775–1855) shared her mother’s love of natural history and continued collecting. Her nephews sent her specimens from Jamaica, including two stuffed crocodiles. Jane left the shells to her niece Sarah Clayton (1795–1880), with the instruction ‘not to dispose of the same in her lifetime and to bequeath the same to some of her Family with a like Injunction’. Sarah lived with her brother, the antiquarian John Clayton (1792–1890). As Jane had hoped, the shells were kept in the family. They continued to be called ‘Bridget’s collection’ but became part of the Clayton Collection, intrinsically linked with the fort and museum at Chesters.

Explore more

-

Bridget Atkinson’s Shell Collection

Explore some of the highlights from Bridget Atkinson’s shell collection featuring items from around the world.

-

History of Chesters Roman Fort

One of a series of permanent forts built during the construction of Hadrian’s Wall, Chesters housed some 500 cavalrymen.

-

Chesters Collection Highlights

The Clayton Collection at Chesters is made up of Roman finds from multiple forts, milecastles and turrets along Hadrian’s Wall.