Want some inspiration on how to spend some of your hard earned holiday? Look to the Romans. They really knew how to relax.

Today people head to spas, shows or sporting events to unwind from the stresses of daily life. It wasn’t too different for the inhabitants of Roman Britain.

Take a trip to the baths

Wealthy Romans had their own private bathing suites (you can still see an example at Lullingstone Villa). But everyone enjoyed a trip to the communal baths. Roman forts like Chesters provided baths for the garrison, and towns had luxurious bathing facilities. There was a huge bathing complex at Wroxeter Roman Town, for instance. For a nominal fee, rich or poor could enjoy facilities that would even put our modern day spas to shame.

Bathing usually began by working up a gentle sweat, maybe by wrestling or playing ball games. Bathers then progressed through a series of rooms, each one hotter than the last. They’d finish in either a very hot, steamy room or a hot, dry room like a modern sauna. Bathers could pay slaves for massages, or to oil their skin and scrape off the dirt with a curved metal tool called a strigil. At some complexes, like Wroxeter, bathers could finish with a refreshing plunge in the outdoor swimming pool.

But the luxury only went so far. The water wasn’t changed very often. And Pliny the Elder recommended a rather disgusting cure for people with kidney or bladder pain – urinating in the pools at the baths.

An artist’s impression of the Hot Room at the Bath House at Wroxeter Roman City in the second century AD.

© Historic England

Catch a show

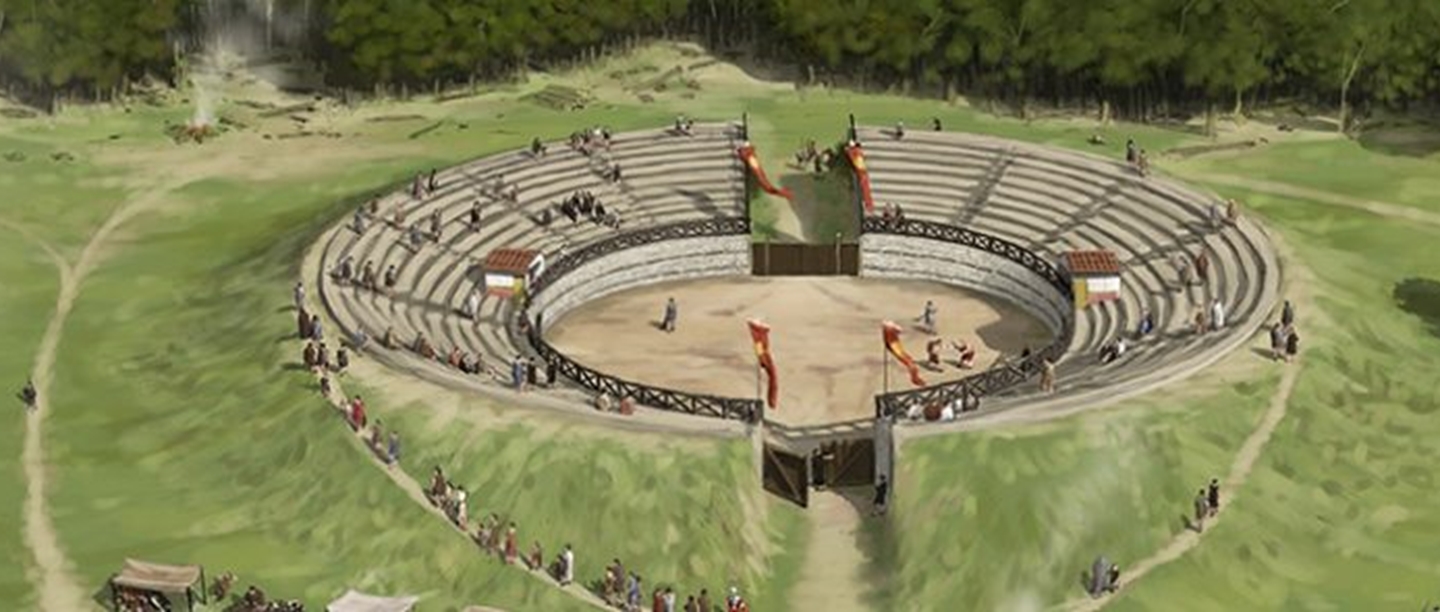

Romans loved spectacles. They were a great distraction from the drudgery of everyday life. Amphitheatres might have hosted gladiatorial contests, or fights between bulls, bears and dogs. You can visit amphitheatres at Silchester and Richborough.

Chariot racing was popular too – an race arena, known as a ‘circus’, has been found at Colchester. During the race, each team represented one of four colours – red, blue, green or white. Supporters followed teams like football fans today. The partisan crowd could even get quite rowdy, especially given the frequent crashes. Successful charioteers became celebrities much like professional sports people today.

Smaller shows at informal venues or the homes of the rich might include acrobats, jugglers and plays. They also enjoyed storytelling featuring historical, or mythical tales. Pantomime was even more bawdy and violent than it is today. But respectable Romans didn’t act, sing or play musical instruments – that was best left to professionals and slaves. Dancing was permissible as long as you were not very good.

An artist’s impression of Silchester Amphitheatre in the late third century AD. By Pete Urmston.

© Historic England

Play a game

The Romans played many board games. Duodecim scripta was an ancestor of backgammon. Ludus lutrunculum was like drafts – the object was to capture your opponent’s pieces. They might use elaborate boards of marble, but simple grids were also scratched out onto stone floors or old tiles. And the pieces could be made from fine materials like glass or bone, or just recycled from broken pottery.

Dice games were cheap and easy to play – perfect for those living in cramped conditions with little free time or money. But fights sometimes broke out, especially since players often bet on the outcome. The poet Juvenal warned of the risk of losing a fortune at games:

‘Men come not now with purses to the gaming table, but with a treasure-chest beside them’.

Despite the illegality of gambling, game boards, counters and dice have been found across Roman Britain, at places like Corbridge and Richborough.

A reconstructed ‘pyrgos’ (dice tower) from Richborough Roman Fort. A dice is placed in the top and bounces

through randomly to prevent cheating. © Historic England

Put on a feast

Wealthy Romans could afford to invite guests to elaborate banquets. The Roman gourmet Apicius lists over 400 recipes for such an occasion, from simple salads to a sauce to accompany boiled ostrich. Wine was served after the food. Falernian wine from Italy was one of the finest vintages. Musicians or dancers provided entertainment. For something more cerebral, the host might initiate a discussion on philosophical questions. The author Plutarch, for example, records a discussion on ‘what came first, the chicken or the egg?’

Hosts wanted to show off their wealth and status, so dining rooms were luxurious. At Lullingstone, the dining couches were positioned in a U-shape around an elaborate mosaic. The room was heated using an under-floor heating system called a hypocaust. Guests reclined while slaves waited on them, even anointing them with perfumed oils!

Feasting in style at home was the preserve of the rich. Most Romans would eat frugally unless they went to taverns or paid to join a private members club. Here they’d find modest yet tasty food – Apicius’ recipes, for example, included something a lot like a burger.

An artist’s impression of the audience chamber and dinning room with mosaic at Lullingstone Roman Villa in the

late-fourth century AD. © Historic England

Lock yourself away

Most Romans would have worked almost every day. Slaves were on constant call to their masters, leaving little time for personal relaxation. But the Romans had work-free festival days so that everyone could pay their respects to the gods. The most boisterous of these was the Saturnalia – a weeklong festival to Saturn starting on December 17th. The order of the Roman world was turned upside down for the week, offering some well-earned respite for Roman slaves – their masters were expected to wait upon them.

And if none of the above appeals, you could copy the Roman writer Pliny the Younger. He made a secluded room in the centre of his villa so he could avoid the Saturnalia festival. While friends, family and his slaves held raucous parties around him, Pliny spent a blissful week surrounded by his books, quietly studying.